Search and Rescue - Put Those Mountain Skills to Use

So maybe you think you've done it all in these mountains, recreation-wise. You've hiked every conceivable trail, climbed the classic routes, spent weeks in the backcountry, bouldered, skied, snowboarded and mountain-biked to the limits of your fancy. You know that you've got a good head on your shoulders, that you've got some skills.

But in introspective moments, you notice you're getting a little weary of the self-absorption and one-up-manship of the adrenaline set. You've got an abundance of energy, aptitude, and good judgment -- but what does it all amount to?

Perhaps it's time to consider another "lifestyle" alternative. Mono County's volunteer search and rescue team holds its annual recruitment meeting in late March or early April, and we are looking for a few good men and women.

What Is SAR?

In Mono County, as in most of the counties of California, the search and rescue team is comprised of volunteers. The Sheriff's Department oversees the team, but all members participating in rescue operations do so for free. Operations leaders here -- the people who coordinate rescuers, equipment and interagency support -- are usually volunteers too.

Mono County's search and rescue (SAR) team is involved in approximately 30 operations a year. The busiest months are July and August, when there are 10 to 12 operations a month on average. In the winter months, there are about four operations a month.

"We aren't just rescuing mountain climbers or hikers," says a long-time SAR member. Rescue operations include just about every imaginable situation.

"We've helped drivers out on the highway; and we've helped people who were out for a little walk when something went wrong. Some of the people we've rescued were in awesome shape, and yet something happened to them anyway; others were in lousy shape and had no business doing what they were doing. They're not all out-of-towners either; some have been locals."

SAR team members are a special, but not necessarily a specialized, breed of mountain folk.

"We're all volunteers -- we don't get paid," says another team member. "We do this because we like to, and we have fun."

"You don't have to be a climbing hero to be useful on the team," he explains. "We'd like to attract people with special skills -- computer, radio, GPS, navigation skills -- but you don't need to know [those skills], because we'll teach them."

A certain level of fitness is necessary, but anyone who is a "competent backpacker" already has the basic skills necessary for the team.

"We want people who feel at home in the mountains," he says, "but not necessarily [people who are] super technically-oriented."

The SAR team also needs people to help organize operations, "people who are very good at doing organizational stuff" -- someone who can "sit in a car, order up helicopters, do all the logistical things necessary during an operation."

A good candidate will be "someone who wants to be part of the team, who has the time to do training, and is available to go on calls."

Winter and Summer

"There's nothing like going on a rescue and saving someone's life," says another team member, "or even helping someone to back out of a difficult situation."

Winter operations for the SAR team involve lost or injured skiers or snowboarders, lost or injured or stuck snowmobilers and stuck vehicles.

Disoriented by white-outs, or led astray by "the allure of making fresh tracks," these people often ski or board down the backside of Mammoth Mountain towards Red's Meadow, ending up either at Pumice Flats or Sotcher Lake. We have erected a set of signs in the area to guide lost people.

The SAR team's procedure in these cases is to send a few rescuers on skis down from above, while others on snowmobiles take the Devils Postpile road the long way around (unless the avalanche danger is high), and try to attract the wayward skiers' or boarders' attention by means of a megaphone and lights.

The increased popularity of Snowmobiling has resulted in more lost or stuck people in recent years.

As for the more gruesome and upsetting aspects of mountain rescue, he says there were modest satisfactions in this as well.

"[When we] recover people who have died in the backcountry, that gives the family closure," he explains.

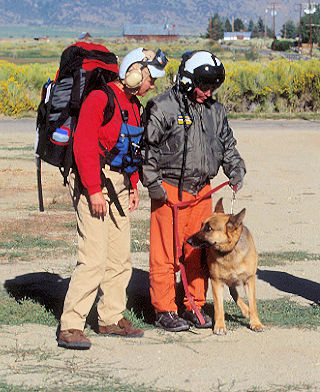

Tracking and More

A team member who works with a tracker dog, says that the search for an elderly man with Alzheimer's was one of her most memorable operations.

Five dog teams were involved on that occasion in the Bridgeport/Twin Lakes area, she recalls, and "the search went on for quite a while."

The operations leader, agrees: "I've seen multi-day searches where searchers get kind of bogged down, and start thinking, 'Oh no, this guy must have left the area.' But everyone who was there [at the Bridgeport/Twin Lakes rescue] stayed focused, and gave 110 percent, 120 percent."

"The area was heavily wooded, and hard to search. It turned out the victim went way beyond where we expected."

The missing man's body was found later by hikers, up a drainage southwest of Twin Lakes.

The operations leader, who has been involved in search and rescue for over 20 years, teaches team members how to track lost people. By reading footprints and other signs, he says, a good tracker can tell all kinds of things about the person he or she is following, including weight, fitness, level of fatigue, and preference for the right or left foot. He says he can even tell the mood -- cautious, determined, angry, distracted -- of a walker.

"It's interesting," he says, "how differently people walk in the same shoes."

Search and rescue teams use "profiles" to help them predict where lost individuals are likely to end up. But he's notices that people who get lost in the High Sierra often wander miles and miles from where they started.

"It seems like when people get lost," he says, "all of a sudden their horizons expand 10-fold. It's like everything's magnified up here."

A Quiver Full of Skills

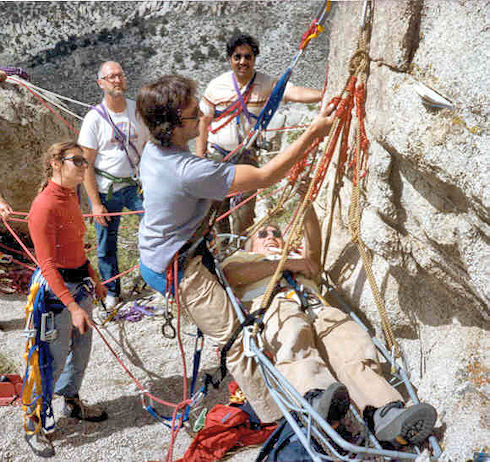

Swiftwater rescue training

Tracking, he says, is only one arrow in the team's quiver.

"It's one of those things you practice a lot, and you only use it a few times a year."

"You have to aid in whatever way you can," he says. "We have so many different disciplines represented on the team. You never know whether it's going to be up your alley, or up someone else's alley."

Dramatic rescues on high and exposed cliffs occur infrequently. "You may need the ropes and rock-climbing skills only a couple of times a year," he explains, "but when you use them, they have to be sharp."

Dog trackers and their trainers, he says, are an example of another SAR team discipline that requires constant work to maintain a high level of preparedness.

"It's incredible how much dedication those dog trainers have," he says. "But all that [dedication] pays off when -- even if only once in a career -- someone gets saved."

SAR members receive training in tracking and search techniques, ropes and knots, search protocols, map and compass use, snowmobile use, avalanche analysis and rescue, ice rescue and more.

"I Wanted to Be on This Team"

Of the 45 people typically on the SAR team's active call-out list, about 25% are women.

"Search and rescue is a field that women should excel in as well as men," says a women team member, who has been a team member for over nine years.

"Primarily, at first, I wanted to be a dog handler," she says, "but in going through the training, I discovered that what I wanted even more was to be on this team. I decided that this was something to do no matter what -- even if the dog didn't become mission-ready."

A relatively new member has already participated in many rescue operations.

"It kind of hooks you," she says. "You feel really good about helping someone."

Although there's no minimum time commitment, she says, "The more you commit to it, the more you get out of it, and the more you can help."

"You're with a group of people who are all caring people," she says. "You truly do get that feeling. [Team members] really look out for each other."

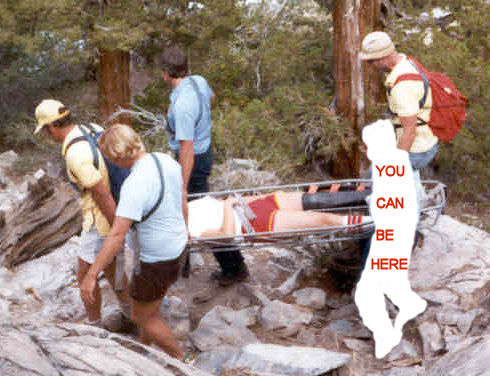

Rescue at Half Moon Pass

Litter lowering/raising training

One stand-out operation was the rescue of an injured hiker at Half Moon Pass, near Rock Creek Lake.

There was a sense among the rescuers that any one of them could have been in the victims place.

"He wasn't doing anything that all of us don't do all the time," she says.

The rescuers (including members of both Mono and Inyo County SAR teams) lowered the victim on belay by stretcher to a flat place, and then kept a fire going through the night to try to keep him warm. A helicopter came at first light.

"That's pretty incredible when you're there waiting all through the night," she says, "and then you hear the sound of the helicopter through the canyon."

Looking back on the rescue at Half Moon Pass, the operations leader says he was struck by "how many people it takes to help one person who's been injured [in the mountains]."

He recalls that "a lot of brute force, and technical systems, and a lot of people" were required to get things done on that night.

One team stabilized the victim, another brought up more medical gear, another bushwhacked a stretcher up the valley from the road.

"Sometimes when someone's in really dire straits," he says, "it can take as many as 30 people in the field [to help them]."

Priceless Service, Low Costs

It costs Mono County a small amount annually to operate the SAR team. The team accepts donations and has several annual fund raisers to collect money for equipment and operations costs.

The team uses three rescue vehicles, several trailers, several snowmobils for winter use. These are stored in our SAR Building that was completed in 2013. The building also has space for team meetings and training.

When helicopters are required to lift out victims, they are called in from the California Highway Patrol out of Fresno or Auburn, Fallon Naval Air Station and the National Guard.

"We have a great working relationship with the helicopter crews," the operations leader says. "They regularly do things that are seemingly beyond what any helicopter crew should be able to do."

The cost of rescues can sometimes be recouped by Mono County, but "SAR [itself] never charges anyone anything," he says.

If a rescued person is from out of county -- but from within California -- Mono County can forward the bill to the county of origin.

The Mono County search and rescue team's annual recruitment meeting is usually held in late March or early April.

You can see more information about team membership here. If you are interested please talk to a team member or e-mail by clicking here: or call the Mono County Sheriff's office (760) 932-7549.