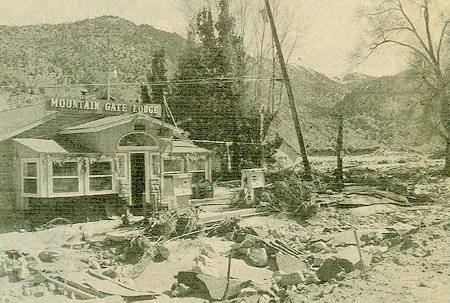

The Mountain Gate Lodge is devastated by January 1997 floodwaters

Mammoth Times/Jane Dove Juneau Photo

On the morning of January 2, 1997, while driving between job sites in June Lake, I monitored a call on my mobile radio from Sheriff Dan Paranick (8A1) to Mono 1 requesting a page for the Search and Rescue team to assist in the rescue of three persons trapped by rising flood waters in Walker, one hour north of June Lake.

I radioed to my employees that I would be responding to the SAR call, and went back to my home for a change of clothes and some gear. On the way out of June Lake I radioed fellow SAR member Sallee Burns to see if she got the callout. She informed me that she had heard the page and would be responding in Rescue 2 after she called a few more team members. I then radioed the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) in Bridgeport and informed them that I was 10-8 to Walker and asked for the specific location of the incident. I was told that it was at the Mountain Gate Lodge on the north end of Walker Canyon. At the time the weather conditions were heavy rain for the fifth consecutive day.

On the way north I heard 8A1 contact the EOC and request a call to the Marine Corps Swiftwater Rescue Team based at the Winter Warfare Training Center at Pickel Meadows. Hearing this request, I knew the situation must be desperate for immediate help. I radioed my ETA to the EOC and got a call back from Sgt. Boa Turner (8S2) requesting that I not attempt any action at the scene until additional team members arrived. Upon arriving in Bridgeport I heard Lt. Cole Hampton (8L1) go 10-8 in response to the situation. Reaching the north end of Bridgeport, I was stopped by a CaITrans roadblock. The sheriff had requested that CaITrans allow rescue personnel through, although the employee manning the roadblock was skeptical that I would make it to the scene via 395. He let me through.

Five miles north of Bridgeport I encountered a 100 yard stretch of the highway that had about 6 inches of water flowing over the pavement. I passed through the flooded section slowly and continued on. As I traveled toward Walker Canyon I heard 8S2 contact the EOC and say that CaITrans would not allow any more SAR personnel past the roadblock. The EOC informed him that I had already been allowed through. I figured the road situation ahead was not going to be very good and that I would likely be turned around. As I approached upper Walker Canyon, a CaITrans vehicle traveling southbound slowed to talk with me. I told him I was responding to a SAR situation and he informed me that the northbound lane was already gone in 5 places and that I should travel quickly on the southbound shoulder of the highway. I continued on, and as I crossed the bridge over the river where the east and west forks meet, the water was about four feet below the bridge. A few miles down the canyon I encountered the first section of missing roadway; a sketch about 100 yards long was completely gone and was replaced by the muddy, raging river. As I continued down the canyon, the current of the river intensified with the drop in elevation, widening from its normal 50 foot wide path to, at times, 100 yards wide. I hugged the western shoulder as tight as possible. I passed additional sections of missing pavement, and about a mile from the scene encountered another CalTrans truck stopped at a huge section of missing pavement. The southbound lane was nearly gone as well, and I quickly drove through on the shoulder. Five minutes later I arrived at Mountain Gate Lodge. It was 1115 hours.

I was met on the scene by Sheriff Paranick and Assistant Sheriff Terry Padilla (8A2). They briefed me on the situation and let me know what to expect as far as other agency assistance. On the scene were some local fire and paramedic crews, a half dozen marines and a lot of spectators. I went to my truck and put on my rain gear, a pair of gaiters, a personal flotation device (PFD), and my climbing harness with a pair of slings and mechanical ascenders. I met with the group of marines who had come from the housing compound in Coleville in response to the situation. They informed me that the Swiftwater Team from the base was out of the area on a training mission. The contingent we had were not swiftwater trained personnel, but were eager to help in any way they could. I also talked with a pair of medics from the town of Walker who briefed me on our victims. We had a husband and wife and their 18 month-old son trapped by high water 100 yards from the highway. I was then led by one of the medics and one marine into the main store and residence (A) of the lodge. The building was completely surrounded by water, which was flowing ankle deep at the frontage where we entered. Making our way to the rear of the home, we came to a stairway that led up to the next floor, as well as down to a split level living area. This area was 4 feet deep in water, completely engulfing the owners furniture and beautifully decorated Christmas tree. We ascended the stairs and made our way to an upper deck from which we could survey the entire scenario.

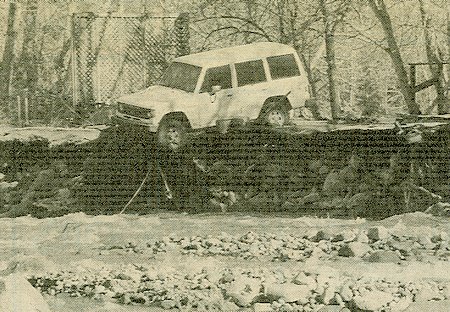

This car's owners are eventually evacuated by helicopter from a cabin at Mountain Gate Lodge

From our deck vantage point I could see the situation was serious. The couple and their child who had rented a small cabin (E), were trapped on a strip of high ground created when the river grew so intense it jumped its bank and fanned out to over 100 yards wide. Here at the mouth of the canyon, the river was at its full fury and growing in intensity by the hour. Upstream from the rental unit two other buildings (F and G) stood on the high ground as well. Water was raging between these three structures and another building (B), which was completely surrounded by swift water and taking tremendous amounts of surge against its south end. Water was raging between our upper deck position and building B, completely engulfing the trunks of four large cottonwood trees growing parallel to the west wall of building B. The depth here was about 6 feet. A small storage building (J) had been washed down river and had become lodged between the northwest corner of building B and the last cottonwood tree. A car and pick-up truck were virtually underwater at the northeast corner of building A. Two small cabins (H and I) to the south of building A were taking huge amounts of surge. Houses C and D were surrounded by shallow, fast moving water. Due east of house C, a 25 foot motorhome was lodged against a small tree by the heavy surge. Once I had surveyed the entire situation, we retreated back through the house to the highway.

Upon reaching the highway, 8L1 arrived with a large inflatable raft. The six marines began unloading the raft and the other gear from the truck. 8L1 asked me what I thought of the situation. I asked him to come out to the upper deck to see the scope of the situation. We agreed that rigging a series of tyrolean traverses from building A to building B could be possible, but rather time consuming. Also, these two structures were taking the brunt of the surge and would likely fail as the day went on. At the time we also had no grappling hook on the scene to use for the rigging. One of the marines went off to his home to retrieve a grappling hook should one be needed. The rescue chopper at Fallon Naval Air Station had been requested but was unable to come due to the heavy rain and low cloud ceiling. 8L1 did not want to attempt any further action until the rest of the SAR team arrived. The road through the canyon was now entirely impassable, so additional personnel were enroute via Smith Valley and out to Topaz Lake, then back south to Walker. This would add well over an hour of travel time.

Back at the highway, 8A1 had requested that a county loader working in Walker be brought to the scene to attempt a crossing. Upon the loaders arrival, I voiced my opposition to this plan to both 8A1 and 8L1. The operator was willing to give it a try. He made an attempt to drive between building A and house B, but backed out almost immediately. The surge was moving the loader and he hadn't even reached the serious water yet.

We began to conceive a plan that would put a team in the raft starting from the south in the pasture area where the water was still shallow. We could actually walk out from the highway into the pasture to a point 200 yards south of building H. We surmised that a crew of four might be able to make it to a point directly in front of the barn, where the barbed wire fence met the barn corner. It looked as if the team could then negotiate fairly moderate water between the barn and building G to reach the high ground. I was hoping that this plan could work so that we could let the two horses out of the barn as well. . The problem with this plan was that the raft would need a belay line to assist in both the insertion and extraction, and a suitable anchor was not available out in the pasture. Any anchor from the road would cause the raft to pendulum back to the roadway. This option was not going to work.

At approximately 1315, the rest of our team arrived, including two experienced water personnel; Shawn Moats and Bob Feiner. They began getting into wetsuits along with the marines. Once Shawn was suited up, I led him into building A to the upper deck location to brief him on the scene. The water between the highway and the front door of the building was now knee deep and very powerful. We were able to cross with some care. We agreed that buildings A and B were in bad shape and should be avoided. We retreated to the highway.

We then decided to go downstream to survey the situation from a point of trees just east of house D. I grabbed the bullhorn from the rescue van and Shawn and I made our way around the north end of house D and out to the trees. Beyond these trees the water was absolutely beyond belief. Just upstream, the motorhome clung to the small tree pinned by the water surge that rose up and over the top of the vehicle. Debris of all kinds raced by, including 500 gallon propane tanks spewing their foul smelling contents. Using the bullhorn, I called out to our subjects (Mr. and Mrs. Forbes) in the cabin and told them we were working on a plan and would notify them when we would be heading their way. They seemed quite calm given the situation, and retreated back into the cabin to stay out of the heavy rain. Bob made his way out to our vantage point and we agreed we should try to get on the roof of house C to see if that would be a good location to mount our rescue attempt.

We traversed around the east side of house D in knee deep water, through a small gate between house D and C and along the west side of house C until we reached a small apple tree at the southwest corner of house C. We climbed the tree, got on the roof, and decided this would be the best spot to mount an attempt to cross the river using the raft. At this point we received word that Fallon Naval Air was able to get off the ground and would be enroute. This was excellent news but we knew that we needed an alternative plan should weather or some other factor turn the chopper back. Shawn put me in charge of rigging the rescue line; somehow we needed to get that line across the river.

Upon returning to the highway, I grabbed a pack full of slings and carabiners and 300 feet of static line. Since we didn't have a line gun to shoot the rope across, I requested a compound bow. One of the medics said he had one at his home and set off to get it. The marines had a light 5 millimeter line to attach to the arrow. I took the rope and the other gear back to the roof of house C and began tying the system off utilizing a large cottonwood tree at the northwest corner of the roof. I tied the two 165 foot lines together and had the system ready to go. The medic arrived back within ten minutes with his bow. Along with me out on the roof at this point were two medics and four marines, who began rigging the light line to shoot across. By the time the line was laid out and ready to shoot, the cord had gotten so saturated with rain that the first shot did not carry at all. Another shot was attempted but the cord was just too heavy. We called to the highway for some fishing line. Within minutes a spinning reel arrived on the roof. The line was secured to the arrow and the first shot was taken. The line paid out beautifully but the shot was way too high and carried over the tree tops to the south of building F. Mr. Forbes could not find where the arrow had come down. We pulled the line back until the line snapped and began rigging for another shot.

While the next arrow was being rigged, I noticed that the water to the east of buildings E and F had risen to the point that a steady stream was undermining the victim's car (V.C.) which was parked between buildings E and F. I called out to Mr. Forbes and requested that he move his wife and son from building E to building F.

Once the next shot was rigged, the medic picked his spot and made a perfect shot. Mr. Forbes grabbed the fishing line. We then fastened the 5 millimeter line to the fishing line and began paying it out while Mr. Forbes pulled. We kept the line as tight as possible to keep it out of the water. The line had to travel about 200 feet over very fast moving water. After a few tense minutes, the line was across and we tied on the static line. I prerigged the static line with two carabiners so that Mr. Forbes simply needed to take the line around a tree and back-clip the carabiners to the rope. After another few minutes the line was across and Mr. Forbes secured it on his end. We tightened the line from our end and were ready for the boat.

Shawn and a contingent of other SAR personnel and firemen carried the boat from the highway across the water directly to the west side of house C and handed it up to us on the roof. At this time the water between the highway and house C was about 18 inches deep and quite swift. Once the boat was on the roof, Shawn joined the rest of us and the boat was lowered off the southeast side of the roof to a team of four who were standing in a small eddy about 18 inches deep. I rigged two long slings and clipped them to the safety line and tossed them down to the raft team to secure the raft to the rope. A 250 foot belay line was attached to the bow of the boat so we could assist from the roof. We had no communication from the chopper as to when it would arrive, so we decided to make an attempt to cross the river.

Bob Feiner and three of the marines got into the raft and began pulling it out into the current with the safety line. The boat team was under great physical stress almost immediately as the current beat on the raft with great force. It took about ten minutes for them to go the first 120 feet to a point just north of building B where a small tree was sticking out of the current. In the lee of building B they were able to make good progress, but upon passing the tree they encountered the second and more severe stretch of swift water which immediately pulled the raft down and around the small tree and trapped it. After struggling for a few minutes to free the raft from the tree and pull themselves back with the safety line, they abandoned the effort and got out of the raft and walked into the eddy behind building B. It was approximately 1500 hours, and within minutes things went from bad to deadly serious.

The three marines and Bob were now standing in a very dangerous position below building B. Water from the upstream side was undermining the building and actually ripping off the siding as it exited the building where our people were standing. If the structure failed they would be crushed and washed downstream. We needed to get them out of there. Presently, the Forbes family was in far less danger than our four guys, so we focused on getting them out. The roar from the water made communicating with the handheld radio to the marines nearly impossible. They made it very clear they did not want to be there anymore and it was time to do something fast. The current had increased since they left our rooftop position only twenty minutes before, making returning by the way they had gone virtually impossible. Suddenly, there was a tremendous explosion as the small storage shack that had been lodged between the tree and building B disintegrated in a deafening roar. The structure and its contents were gone in seconds. It was a desperate situation that called for a miracle. Suddenly, we heard the familiar thump of the helicopter rotor blades as Fallon Naval Air turned the corner and flew up to our position. Now the noise in the air was really extreme as the chopper did fly-bys to test the wind. They came around and began to hover over the Forbes family and their rapidly disappearing island of safety. We radioed the chopper to go after our people first since their situation was far more critical. Once the chopper moved over our guys and began lowering the winch cable, the six of us on the roof decided it was our turn to get out.

The water between us and the highway was now 3 feet deep and full of debris, flowing between 25 and 35 miles per hour. The team was busy moving vehicles down canyon as the highway now had nearly a foot of water flowing down it. Before leaving the roof, I retrieved my ascenders from the boat belay line and clipped them to my harness. We climbed off the roof in two groups of three; two marines and one of the medics first; followed by Shawn, myself, and another marine. Climbing down the little apple tree at the corner of the roof, I realized we were in a desperate situation ourselves. We made our way through waist deep water to the gate between house C and D. The current was very strong here as it ripped through the gap between the houses. At this spot the 2 marines and the medic locked arms and waded out into the current. Halfway out they were swept from their feet but were able to grab safety lines thrown to them by other team members who were now standing in a foot of fast water trying to assist us. Shawn and the other marine and I made it across the flow between houses C and D and began traversing along the west wall of house D. We were able to hold onto the raised siding boards of the house and walk on the top of a 3 foot high rock veneer that was part of the structure.

Halfway down the length of the house (D) was a 30 foot tall cedar tree (1) about 18 inches in diameter. Straight out from this tree towards the highway was another tree (2) of equal size. Shawn jumped from the wall and went for the tree (2) and made it into the tree's eddy. He yelled back instructions to myself and the marine to follow him to the eddy, then jumped in and swim for the safety lines when they were thrown towards us. Shawn launched into the water and was immediately swept downstream, but managed to grab a throw line and was hauled to the highway. Reluctantly, I went for the tree (2) and just managed to grab it as my feet were swept from beneath me. Because I was not in a wetsuit, I was extremely cold and very uncomfortable with the thought of jumping into that debris laden current. My clothes felt like they weighed 50 pounds and I was certain I would sink. My boots were full of water and felt like anchors. I decided I would not commit to the swim until one of the team members had gotten a rope to me first. However the water was coming up so rapidly now, our safety people were forced farther and farther away from me, making the rope toss more difficult. The desperate look on their faces told me I was not going out that way.

With my arms wrapped around the tree, my hands had been under water for nearly ten minutes and were completely numb. Even if they would have gotten the rope to me, I doubt if I would have been able to hang on. Suddenly a large chunk of debris slammed into the tree just above my hands and lodged there, creating a huge dam that forced the water around the tree on either side some two feet above my head. It was time to get out of there, so I began to climb. After climbing a few feet I yelled back to the marine who was clinging to the tree (1) next to the house to climb up the tree and get on the roof of the house. I'm sure the desperate look on his face equally matched my own. My hands were unable to grip the slippery branches of the tree, so I climbed by hooking the branches with the crook of my wrist. Once I got up the tree to a point where my feet were out of the river, I was desperate for a rest. I took the two slings that I had on my harness and tied them off to the tree trunk, clipped myself off to my harness, and slumped into a ball. I unzipped my parka enough to get my hands down into my chest area to try and revive them. My fingers were ashen white and would not function at all. I looked over at the marine, who had made it onto the roof and was clinging to the chimney and watching the chopper pluck our guys from their position. I was glad to see that Bob and the 3 marines were now safely to the highway and the chopper was maneuvering once again to extract the Forbes' from what was left of their refuge.

After 10 to 15 minutes, my hands began to go through the awful pain of rewarming, but I was grateful for the feeling of any sensation at all. I began seriously contemplating my options should the chopper not be able to get to me. It was getting dark and I knew the chopper must be getting low on fuel. There was a good chance they wouldn't be able to get to me and the marine on the roof. I was also concerned about the integrity of the tree I was in. It would shudder violently every time it was struck by debris in the water. The branches of the other tree were 10 feet away, and the marine had no rope or other equipment with him. As the water continued to rise, I climbed higher up the tree to keep my feet out of the water. I was running out of tree. I suddenly realized that I was high enough in the tree to where I was equal in height to a steel cable that was connected to utility poles both down and upstream from my position. The steel cable was a support line for the cable TV supply line.

Leaning out from the tree on my tie-off sling I could actually touch the cable. I could see the utility pole downstream; it was enveloped in water at its base, but within ten feet of our people on the highway. I could not see the upstream pole, but I knew it had been surrounded by water all day and was probably getting more and more insecure by the minute. I was also concerned about the strength of the cable attachment point on the pole and whether that anchor would support my weight. I would have to reach out and clip one of my slings to the cable, then release from the one sling on the tree, suspending myself from the steel cable and allowing me to traverse the line about 70 yards downstream to the utility pole. Had I been given any information that the poles looked secure, I would have chose this option to a second. I wanted out of this river in a bad way. I decided the option was very risky and would serve only as a last resort should the tree begin to go.

Suddenly I heard my radio crackle from it's position in my chest harness. I pulled out the microphone and addressed the caller. It was 8L1 asking me if I had a spare set of keys to my truck because a team member attempting to move it had just locked the keys in it with it running. This seemed like such a ridiculous question given my present condition both mentally and physically. I looked down the highway and could see my truck sitting in the middle of the pavement surrounded by 2 feet of swift, muddy water. I told 8L1 to find a slim jim or bust a window; just get it out of there. In reality I didn't give a damn about the truck and actually found myself taken aback that they would even concern me about a truck at a time like this. I watched as my fellow team members backed farther and farther away from me, and my heart sank into desperation. I began to feel like my situation was hopeless and unless that chopper made it back I was going to die in that river. The water rose, I climbed higher, it got darker, and my body got colder. I'd been in the tree for 45 minutes. The chopper had gotten the Forbes family out and disappeared. I stared at the water below me and figured that they would probably never find my body amidst all the debris. A large crack jarred my senses as the barn with the two horses in it disintegrated 100 yards away and disappeared into the blackness. My nerves were running pretty thin. Then I heard the chopper.

As the chopper approached, another house below house D cracked and disintegrated into the river. My adrenaline was working overtime. Through my radio I could hear 8L1 telling the chopper that there was a man on the roof and one in the tree. I strained to hear my radio as the chopper entered into a hover directly over my position. It was nearly dark and the chopper had a powerful search light pointed toward us. I leaned as far as I could off my tie-off so the chopper could see the white helmet I was wearing and determine my position. After hovering a few minutes they moved off a bit and I could hear the radio again. I heard the chopper tell 8L1, "We can get to the man on the roof, but the guy in the tree is directly below the high tension lines and we can't get the winch cable to him." My heart sank. I looked up and could see the power lines 20 feet directly above me. My mind began to race with options. I looked at the cable and thought of going for it. Then I remembered I had my mechanical ascenders attached to my harness. I radioed 8L1 and he repeated the message from the chopper and said they couldn't get to me. I replied, "The hell they can't!" I was not about to be left there. I told him to tell the chopper to get a rope to the marine on the roof, and I would take care of getting to the rooftop.

As the chopper circled, I yelled to the marine that they were going to lower a rope to him and that I needed him to tie it off to the chimney (C.H.). Though we were only ten feet away from each other, he couldn't understand at first. After a few minutes, he grasped what I was yelling to him and the chopper got into a hover and lowered the rope. I watched as the marine, with his hands desperately shaking from the cold and the fear, wrapped the chimney and tied off the line. I instructed him to come to the edge of the roof and throw the line through the branches of the free that was up against the house and out to me in my tree. He made a perfect throw, and I hauled the line in. I attempted to tie a knot to clip in to my harness, but my hands were still pretty useless. Then I remembered the ascenders. I clipped off both ascenders to my harness and secured them to the rope. With their rope gripping ability, I was free to simply jump and be held on the rope by the ascenders. Without thinking twice I slid the ascenders up the rope as far as I could, and jumped. I swung across the ten foot gap, over the water, and crashed heavily into the branches of the other tree. With the rope's stretch I had dropped enough in the arc of the swing that when I came to a stop, my feet were back in the water. The current ripped at me and pulled me away from the base of the tree, but I was able to claw my way up the branches with my wrists and get on the roof. I quickly detached the ascenders from the rope and joined the marine at the chimney for a much needed bear hug. Then I realized how much the building was shaking from the force of the water. We wanted out of there in the worst way.

The chopper got into a hover 20 feet above us and lowered a crewman bringing harnesses. Since I already had one on, I wasted no time clipping in to the winch cable. A rescue harness was put around the marine and clipped into the cable as well. I wrapped my legs around the marine and we were winched up into the chopper. We were dragged through the open side door and the cable was sent bock down for the crewman on the roof. A few minutes later he was winched into the chopper, and we were bound for the Operations Center set up at the Walker Community Center. The chopper set down in the ball field a few minutes later, and as we made our way to the warmth of a building and hot food, I was amazed at how firm the ground under my feet felt. Entering the community center with questions of why I would ever put myself in this situation, my eyes locked on a young couple wrapped in blankets, eating a warm meal, and holding their chubby little 18 month-old son.

Epilogue:

In the weeks that followed the events of January 2, 1997, it was determined that the Walker River, with its normal flow rate of 700 cubic feet per second, had on that day come through the Mountain Gate Lodge complex at over 14,000 cubic feet per second. Fly overs the next day determined that 8 miles of U.S. 395 was completely destroyed, and the Mountain Gate Lodge was all but obliterated. The entire Walker community suffered huge losses, with homes totally washed away, including the top ten feet of soil from many properties. Other properties had huge amounts of debris and mud deposited on them, rendering them completely destroyed of their value. Damage estimates were put in the area of 75 million dollars. Some families lost everything they owned save for the clothes on their backs. And like so many of the victims in Walker, the owners of the Mountain Gate Lodge lost their entire investment and possessions, without the benefit of flood insurance.

The citizens of Walker continue to try to put their lives back as best as they can, while contractors war against the river to try and rebuild the 8 miles of what was a very scenic stretch of highway and a major artery serving the citizens of Mono County.

A few weeks after the events at Mountain Gate, I made my way back to Walker via the detour through Nevada. I could never have imagined what I saw as I pulled up to the front of the complex, or what was left of it. Of the 11 buildings in the complex, only three remained; and only pieces of those at best. Where the water had been raging between the Forbes' little island and building B was now a 12 foot deep, 60 foot wide swath of river bed strewn with rocks of every size. Amazingly, where the three structures had stood on the small island, only the Forbes' car remained, standing on its front bumper after falling into the deepening river channel. The section of house C that we had been working off of was entirely sheered away. House D remained mostly intact, although listing at a skewed angle off ifs foundation and packed full of mud and rock.

As I surveyed the awesome destruction left by the raging river and walked across areas that were visions of death just a few weeks prior, I was struck by the fact that not a single person was hurt or killed; not here at Mountain Gate or anywhere in the entire flood ravaged county. Our efforts to rescue the Forbes family might best be described as a successful failure. We went up against incredible odds, made some mistakes, got lucky on many an occasion, and lived to tell about it and learn from the experience. Had it not been for one very professional helicopter crew and their impeccable timing, in all likelihood 9 people would have lost their lives, including myself.

As for me personally, the events of that day touched my life deeply. I know that my prayers were answered when I asked my God to spare me from a horrible death in those dark, raging waters. That I was given another chance to accomplish the things in my life that God has set before me is a great blessing. And to have the chance to live life with my wife and two kids and help them grow is to know what joy truly is. So many factors played a part in me coming out of this event alive, one can't deny that there is, a God. Had I not put on my harness that morning, or grabbed the ascenders from the rope and taken them into that tree with me. Had the marine not been on the roof to tie off that line, or the chopper been unable to assist. So many factors that added to the puzzle that pieced together an escape route. I know I am a blessed man.

A few months after the events at Mountain Gate, I attended a 3 day Swiftwater Rescue Training Course on the Truckee River in Reno, Nevada along with three of my team mates. I gained a great deal of insight and knowledge on how to deal with the forces we encountered on the Walker that day. I know that if I was faced with the same situation today, I would feel far more confident in dealing with those conditions. A little schooling and gleaned knowledge goes a long way when dealing with an element that you do not have control over.

Above all I am grateful to my fellow rescue team members, who stood against the odds that day and gave it all they had, and though forced back in their attempts to assist me in getting out never gave up hope that I would get out alive. And they did rescue my truck.

On my day at Mountain Gate to survey the damage, I went over to see my tree that for an awfully long hour was my only comfort. The water had taken it away.

Dean Rosnau

February 1997