Val Ice shows off the emergency blanket that she says 'saved my life'

Erick Sugimura Photo

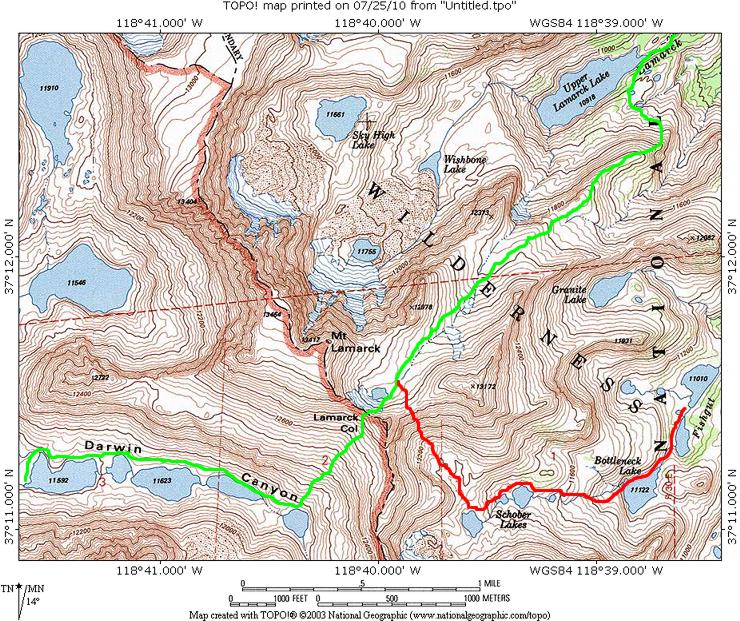

Valyrie "Val" Ice and two friends set out on the Lamarck Lakes Trail from North Lake above Bishop on Tuesday, July 13. The plan was for Ice's friends to day hike with her to a campsite where she would spend the night, then continue on alone across the Lamarck Col (a steep, high pass) into the Darwin Canyon area the next day.

Ice was carrying an eight-day food supply for two other friends who were traveling a section of the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT). She would drop the bear canister of supplies in a predetermined location near Darwin Lakes and hike back to her camp on the sandy flat on Wednesday, then leisurely hike out sometime Thursday or Friday.

But in the backcountry, unanticipated conditions, errors in judgment, small mistakes and even the rational mind have compounded and led many a backpacker awry with serious, even fatal, consequences.

"I was in over my head," Ice said. "I'm not in shape [for multi-day trips with extra weight.]"

Ice, a Mammoth Lakes resident of 21 years and teacher at Edna Beaman School in Benton for the last five years, is an experienced day hiker, but had only done a couple of overnight trips by herself in the backcountry and this was her first time going cross country (off-trail). Still, she had a topographical map of the area on which her friends had hand-drawn the route she should take to cross Lamarck Col.

"This is probably the most popular cross-country route across the Sierra crest between Bishop Pass and Piute Pass ... But this is still a long, arduous route, and it should only be attempted by hikers in good condition." [excerpt from "The High Sierra - Peaks, Passes, and Trails" by R.J. Secor]

Tuesday, July 13

Ice and friends easily made it to the sandy flat where she would camp that night. Her friends turned back toward Bishop, which was visible from there. Ice even made a cell phone call to her husband Willie Harder to say how beautiful it was and let him know that she would be back on Thursday. She noticed that her phone's battery was low, but forgot to turn it off overnight.

Wednesday, July 14

Starting early, Ice was supposed to drop the supplies off for her friends on the PCT between 10 a.m. and noon. If the timing worked out, she might even meet them. She left her sleeping bag and tent, planning on being back well before nightfall.

Unaccustomed to the weight of so much food in her pack, the hike up toward the col was slower going than she expected. Ice exchanged words with a climber coming down from the col who asked if she had crampons and an ice axe. She only brought her ski poles.

"Good luck," she recalled him saying.

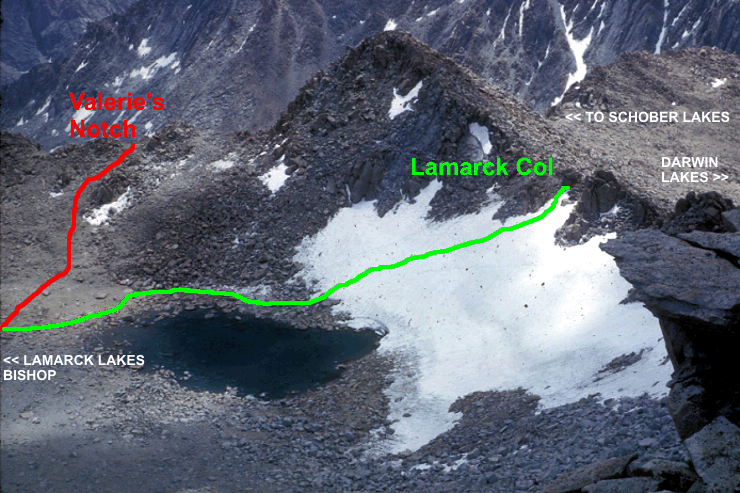

Below the col, Ice saw the ridge and a huge snow field. There were footsteps in the snow leading straight up, but the climber's words had unnerved her slightly.

"I looked to the left along the ridge and saw a notch. I assumed that the whole ridge would drop me down to the other side," Ice said. "That was my first big mistake."

GREEN is the intended route - RED is estimated route Valarie took

When Ice had climbed up the easier route to the notch, she looked down the other side at a steep descent, like a couloir (a steep chute, often with snow or ice).

"Instinctively, I knew it wasn't right," she said. But her rational mind was telling her that she was in the right area. There were lakes below, but her map didn't jive with what she saw. She was physically tired from carrying the extra weight and the need to deliver these supplies for her friends on the PCT was weighing heavy in her mind.

"In my better judgment, I would never have done it," but her friends were seven days on the trail and relying on her to make the drop off.

So, Ice found herself pushing scree down the pitch, sliding down on her rear end. Halfway down, it became a snow field; a moraine filled with boulders ten feet high and huge cracks in the ice.

"I was terrified," Ice said, thinking that sliding into a boulder or falling into a crevice would very likely leave her injured or trapped.

Her path eventually led her down a series of rocky ledges, but as she went she kept finding more and more lakes. She was supposed to leave the supplies on the west side of the lowest lake, but at the fourth lake she started to feel panic.

"I sat there and I was yelling," she said. "Obviously, no one answered."

There was another lake further down, so she struggled on wishing that she'd brought her sleeping bag. The way down had been so difficult, in her mind she felt going back that way was not an option and she would be spending the night somewhere in what she still believed was Darwin Canyon. Ideally, she would run into her friends and spend the night with them.

Later, however, Ice would learn that the lower notch she had taken beneath Lamarck Col had actually brought her to Schober Lakes, still on the east side of the ridge from Darwin Lakes where her friends on the PCT spent most of the day waiting to meet her.

It was about 4 p.m. when Ice came to a sixth lake. "I thought, 'This has to be it!'"

She dropped the burden of the supplies she'd been carrying and tied a red flag to a tree to mark the location for her friends.

Exhausted by this point, she saw a small crevice under a rock. "I thought, 'This is where I'm going to spend the night.'"

It was a green meadow area, there were clouds of mosquitoes, but luckily Ice had everything for her trip with her aside from her tent and sleeping bag. She had food, a poncho, an extra t-shirt, water pump, headlamp and, most importantly, an emergency space blanket. Wrapped in that thin, silvery sheet, she was able to pass the night shivering, but not with too much trouble.

"That thing saved me," she said.

Thurday, July 15

When Ice got up on Thursday morning, she felt physically better and, released from the driving need to deliver food to her friends, able to think clearer.

"I had more control of myself," she said, knowing that her best bet would be to go back up the way she had come down. "I thought, 'I need to be super careful. The only one who is going to get me out of here is myself.'"

Turning back towards the ridge, she saw a pathway of beautiful wildflowers. Following the rough path, she came across the occasional scat that told her she was on a deer path.

"It was a little easier going up," she said, but she couldn't recognize where she had come down the day prior. Eventually, she came across some of her own footprints.

"I tried to leave a path [on the way down]. I'd step in the mud on purpose."

Ice focused on taking 'baby steps' - take three steps, then a breath, then repeat - something she'd used in 1996 when she climbed Mt. Kalapatar (17,800 feet), across the valley from Mt. Everest.

Slow and steady, mindful of being extra cautious, she made her way back to the first lake by early evening. Her phone had long since shut down, but she knew that if she left it off and could get high enough, she could try powering it on and possibly get a couple seconds to call for help.

She also knew that she wouldn't be able to climb up the couloir that she had come down that night. And thunderclouds were building.

Choosing to save her strength, she found a sandy bench and a rock with another crevice to slide into. Wrapped in her space blanket, she stayed there while it rained and thundered on and off through the night.

While Ice had been making her way back towards the ridge, her friends at Darwin Lake travelled over Lamarck Col twice, trying to find out why Ice had not met them or dropped off their supplies. It wasn't until they found her empty campsite that they called Ice's husband.

"I was really scared," Harder said. "I wouldn't have been worried until Friday night [if I had not heard anything] because she could've decided to stay an extra night or something, but they said it didn't look like her camp was used that night."

Harder knew that there wasn't much for him to do from the other end of the phone and it still seemed reasonable that Ice might show up on her own at any moment. Their friends searched the surrounding area a little longer before the decision was made that Harder should contact Inyo County Search and Rescue (SAR).

"The SAR guys were really good. [Inyo County Sheriff's] Deputy Winkler and [Kings Canyon Natl. Park District Ranger] Ned [Kelleher] communicated constantly with me," Harder praised. "Their response was immediate. Thursday, they got things lined up, but they couldn't do much [because of thunderstorms in the area]."

And despite the mobilization of the SAR teams, Harder's only link to the area was via cell phone to their friends. He started thinking of the snowfields and all the hundreds of possibilities of what could have happened to his wife.

"I was scared out of my mind."

Friday, July 16

An early morning break in the thunderstorms allowed the SAR team to send in a small helicopter to pick up four Kings Canyon backcountry rangers who were in the surrounding wilderness and deposit them in Darwin Canyon to search for Ice.

Ice woke up to combined impact of the bad weather and the imposing climb to get out.

"I felt like a prisoner down there," she said.

In what was most likely the same break in the storms that allowed the SAR helicopter to fly, Ice decided to make her move.

"I'm rock climbing to get out of there," she said of the effort.

Moving laterally and up, she saw what looked like a natural dirt path. Making her way towards that, she heard someone at the very top of the couloirs shout down, "Hello! Are you Val?"

It was a married couple that was backpacking in and had even spent the night with Ice's friends at the sandy flat where Ice's camp was. The husband set off running to tell Ice's friends that they'd found the missing hiker while the wife remained to monitor Ice's progress.

"Just to know that someone was looking at me... it was a light of encouragement," Ice said of that moment.

A little while later, there were suddenly two climbers next to Ice, who just happened to be climbing in the area. One took her pack and they guided her up, encouraging her.

"I think I found religion while I was down there," Ice said. "They were my angels."

Once told that Ice was found, her friends were able to notify SAR just in time to stop the Chinook helicopter loaded with around 18 search and rescue personnel that was about to take off.

"I was so thankful," Ice said of everyone who had been part of the search for her - from four complete strangers hiking and climbing in the area, to her friends, to the SAR personnel, to her husband - and to all her friends in town who heard she'd gone missing and had been offering their thoughts and prayers for her safe return. "I was just overwhelmed."

Back home in Mammoth, Ice has only a pair of scrapped legs to show for the ordeal and is otherwise none the worse for wear physically. Her husband, friends and family are as grateful for her presence as she is for their support.

"It was a harrowing experience. I was pretty scared," she said in retrospect. "There were so many mistakes that I made that just kept compounding."

While admittedly not an experienced backpacker or cross country traveler per se, Ice is not unfamiliar with hiking through the mountains and wilderness of the Eastern Sierra. In this sense, she is not so different from many of the individuals who head off into the mountains with fully-loaded packs, trekking poles in hand.

"You don't think it's going to happen to you."