The following article with its supporting references gives a very complete scientific analysis of the problem. It is very worthwhile reading. You will probably be surprised at the author's conclusions. His "drink smart" recommendations are worth following.

Update December 2004 - Read here about recent studies from the UC Davis School of Medicine with similar conclusions.

Introduction

Ask the average outdoors person about Giardia lamblia, and they have certainly heard about it. Almost always, however, they are considerably misinformed about both the organism’s significance in wilderness water and the seriousness of the disease, giardiasis, if contracted.

The amount of information easily found on the subject is voluminous. Unfortunately, almost all of it is flawed in important aspects, being unsubstantiated, anecdotal or speculative. Official informational publications put out by the United States government are far from immune to this criticism.

This paper is the result of a critical distillation of relevant articles, retaining only those from scholarly, peer-reviewed, or otherwise professional and trustworthy sources.

One conclusion of this paper is that you can indeed contract giardiasis on visits to the high mountains of the Sierra Nevada, but it almost certainly won’t be from the water. So drink freely and confidently. Proper personal hygiene is far more important in avoiding giardiasis than treating the water.

First, an excerpt written by a highly regarded wilderness physician:

“In recent years, frantic alarms about the perils of giardiasis have aroused exaggerated concern about this infestation. Government agencies, particularly the United States Park Service and the National Forest Service, have filtered hundreds of gallons of water from wilderness streams, found one or two organisms (far less than enough to be infective), and erected garish signs proclaiming the water ‘hazardous.’”[2]

And another, by researchers who surveyed the health departments in all 50 states and scanned the medical literature looking for evidence that giardiasis is a significant threat to outdoor people:

“Neither health department surveillance nor the medical literature supports the widely held perception that giardiasis is a significant risk to backpackers in the United States. In some respects, this situation resembles (the threat to beach goers of) a shark attack: an extraordinarily rare event to which the public and press have seemingly devoted inappropriate attention.”[3]

I first explored this subject in 1987[4] and again in 1996[5], with an update in 1997[6]. The emphasis has always been to waters of the High Sierra—“High” meaning elevations of 8,000 or 9,000 feet and above—but much of the material applies to wilderness water at lower elevations and beyond the Sierra.

Since 1997 a wealth of additional information resulted in a follow-on paper[7] that was not published in the usual sense, but was made available to several mountaineering and hiking organizations. As even newer data became available I incorporated it, keeping the same title but amending the date. These various versions were picked up by a number of additional websites,[i] and have migrated further.

In 2002, having seen the paper on one of these websites, an editor at National Geographic Adventure magazine contacted me for details. The staff at NGA then independently examined the information and research, and wrote their own article.[8] That article verified the findings of this paper.

From the beginning, the conclusions have always been that “the Giardia problem” in the High Sierra and elsewhere is grossly exaggerated, and that virtually all of the few cases of giardiasis subsequent to wilderness visits are wrongly blamed on the water. After incorporating the most recent information, those prior conclusions are not only still valid but also considerably reinforced.

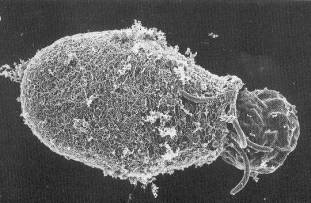

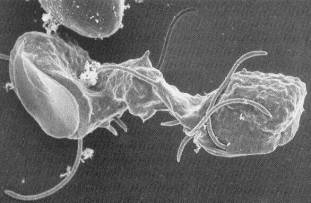

Just who is this little guy, anyway?[ii][9], [10], [11], [12], [13]

The parasite Giardia lamblia, now known also as G. intestinalis or G. duodenalis, was first observed in 1681 by Anton van Leeuwenhoek, inventor of the microscope. It was named in 1915 for two scientists who had studied it: Prof. A. Giard in Paris and Dr. F. Lambl in Prague. There are species of Giardia other than G. lamblia (e.g., G. muris) that infect small rodents, amphibians, birds and fishes, but they aren’t passed on to humans and most other mammals.[14] This paper deals exclusively with G. lamblia.

Giardia is a flagellated (having whip-like appendages for locomotion) protozoan that, in the trophozoite (active) form, attaches itself with an adhesive disk to the lining of the upper intestinal tract of the host animal. There, it feeds and reproduces. Trophozoites divide by binary fission about every 12 hours, so a single parasite can theoretically result in more than a million in 10 days and a billion in 15 days.

At some time in its active life, the trophozoite releases its hold on the bowel wall and floats in the fecal stream. As it makes its journey, it transforms into an egg-like structure called a cyst, which is eventually passed in the stool. Duration of cyst excretion, called shedding, may persist for months. Once outside the body, the cysts can be ingested by another animal. Then, they “hatch” into trophozoites due to stomach acid action and digestive enzymes, and the cycle repeats.

The trophozoite is 9 – 15 microns long, 5 - 15 microns wide, and 2 - 4 microns thick. Unlike the cyst, it cannot live for long outside a host.

Cysts are 8 - 12 microns long by 6 - 9 microns in diameter, so a million could fit under a fingernail. Cysts can survive for as long as 2 to 3 months in cold water, but they cannot tolerate drying or freezing.12, 13, [15], [16], [17], [18] They are also destroyed by UV radiation, heat and biocides such as bleach.15

A significant infestation can leave millions of trophozoites stuck tight to the intestinal lining. There, they cripple the gut’s ability to secrete enzymes and absorb food, especially fats, thereby producing the disease’s symptoms. The symptoms typically appear one to two weeks after ingestion, with an average of nine days, but four weeks is not uncommon. Symptoms can vanish suddenly and then reappear. They may hide for months. They may not appear at all.13, [19]

There are three ways that giardiasis, the disease caused by Giardia infections, can be contracted: contaminated water, contaminated food, and direct fecal-oral. A person who has just come down with the disease and who wishes to identify the source needs to reflect on not only the possibility of each of these pathways, but in a suspect period ranging from typically one week earlier to four weeks earlier.

The bad news: Giardia lamblia is everywhere 2, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]

Giardiasis has been most often associated with travel to such places as Latin America, Africa, Asia, and the former Soviet Union. However, Giardia has always been present in wilderness streams, in the water supplies of most cities around the world, and even in the municipal water of large U. S. cities. In fact, in the 1930s and 1940s, before regulated municipal water treatment plants, we were all ingesting Giardia all the time.[27]

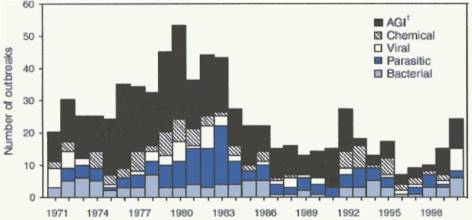

Giardia lamblia is the most commonly diagnosed intestinal parasite in North America.31 It is the most frequently identified cause of diarrheal outbreaks associated with drinking water in this country. To be classified a disease outbreak, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) must have implicated the source, and there must be multiple cases. For 1999 – 2000, there were 39 drinking water disease outbreaks (all causes) in the US, involving 2068 persons. [28] This is an average of 53 persons per outbreak, but sometimes a single outbreak can be devastating: In 1993, Cryptosporidium managed to get through Milwaukee’s water treatment system and sickened 403,000 people.[29] We take drinking water for granted in this country, but it is far from being completely trustworthy.

Figure 3. Number of Drinking Water Disease Outbreaks, by Year and Cause28

(AGI = Acute Gastrointestinal Illness of unknown cause)

Estimates vary, but fully 20 percent of the world’s population have giardiasis, and 4 to 7 percent of Americans, most without any symptoms at all.13, 15, 16, [30] The CDC estimates that as many as 2,500,000 cases occur in the US, or about one for every 100 persons—every year.[31]

Infestation rates of 50 percent of the children in day care centers across the country have been noted, with many being asymptomatic.[32] Institutions for mentally retarded persons can have high rates. Other high-rate populations include promiscuous male homosexuals, international travelers, and patients with cystic fibrosis. And family members of these individuals.

In an incident in New Jersey a child had a “fecal accident” in a community swimming pool, and nine swimmers came down with the disease.[33] How many Giardia cysts might have been involved? The number of cysts shed in feces is highly variable but has been estimated as high as 900 million a day for a human.24

Municipal water utilities must use filters to remove the organism. San Francisco city water, coming primarily from the Hetch Hetchy watershed in Yosemite National Park, tested positive for Giardia about 23 percent of the time in 2000, although at very low levels: fewer than 0.12 cysts per liter[iii]. This water is of such high quality that the US Environmental Protection Agency and the California Department of Health Services have granted Hetch Hetchy water a filtration exemption, meaning that filtration treatment to ensure its safety from Giardia and other organisms is not required.[34]

The city of Fairfield, 45 miles northeast of San Francisco, stated in 2001, “Giardia cysts were detected three times at levels of 0.19, 0.21 and 0.50 cysts per liter. At these levels, the source water is considered an insignificant risk for Giardia.” [35]

The Los Angeles Aqueduct, which transports water to that city from the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada—where many wilderness visitors obtain their water directly—averages an even lower 0.03 cysts per liter.[36]

Of course, there are contaminants other than Giardia to worry about, and most water districts treat their water before distribution.

Drinking contaminated water is one way to get the disease. Less common in developed countries is direct passage from stool to the hands of a food preparer and then to the food itself. When 16 people got sick from the salad at a Connecticut picnic, the CDC tracked the source to a woman who had mixed the salad with her hands. She didn’t have giardiasis, but one of her children did—without any symptoms.19 A similar situation occurred in New Jersey, with the salad preparer testing positive for Giardia along with her child and pet rabbit.[37]

There is accumulating data that Giardia is one of the most common parasites of companion animals throughout the world. The problem is greater in multi-pet homes, due to the ease of infection from one pet to another—more so if the pets come in contact with animals outside the home.14 And, because of the generally close and frequent contact with their pets, it is easy for infections to flow to household members.

Commercially prepared food can sometimes be tainted if it is moist and not cooked. For example, one outbreak of giardiasis was traced to Giardia in canned salmon.[38]

Contaminated food may be an unlikely source for the general population in this country but,for wilderness visitors, it may be the most common one. Put another way: If the water is clean—a topic explored in this paper—food-borne and direct fecal-oral routes are the only pathways.

On a climbing expedition to Tibet in 1993, members of our party came down again and again with what was undoubtedly giardiasis. Our water came from glacial melt, but all our food in advanced base camp and below was prepared by Sherpa cooks. Most of the food they prepared—potatoes, rice, cauliflower, cabbage, onions—came from Nepal. We were continually assured that the cooks were practicing good hygiene, yet we had major intestinal problems that prevented many of the participants from getting high on the mountain.

The disease has been referred to as “beaver fever” because of a presumed link to those water-dwelling animals known to be carriers. However, it now appears that it is more likely that humans have carried the parasite into the wilderness and that beavers may actually be the victims. In particular, there is a growing amount of data showing that beavers living downstream from campgrounds have a high Giardia infection rate compared with a near-zero rate for beavers living in more remote areas.

In either case, beavers can and do contract giardiasis. Being water-dwellers, they are able to contaminate water more directly than an animal that defecates on the ground.

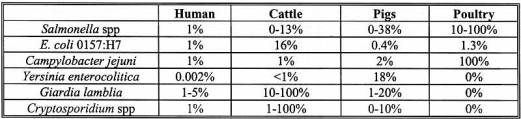

Table 1. Prevalence of Enteric Pathogens in Humans, Cattle, Pigs and Poultry16

Other animals that can harbor Giardia lamblia are bighorn sheep, cats, cattle, coyotes, deer, dogs, elk, muskrats, pet rabbits, pigs, raccoons and squirrels. But naturally occurring infections have not been found in most wild animals including badgers, bears, bobcats, ferrets, lynxes, marmots, moose, porcupines, skunks and wild rabbits. Horses and domestic sheep were once thought to be Giardia-free, but more recent studies have shown that they can be infected.15, [39], [40]

Most strains of Giardia lamblia in animals can cause human infections, but some (e.g., in pigs) are apparently unlikely to do so.16

If “It’s everywhere!” why is it not more of a problem?

The good news: Most of the time, the concentration of Giardia cysts is very low 2, 9, 11

Outside of places where “fecal accidents” occur, dirty diapers congregate, and cities where water treatment plants break down or are ineffective, there is little room to worry. A few Giardia cysts will cause no harm, and in fact may be useful in acquiring immunity to the disease.

How many cysts does it take to get the disease? Theoretically, only one. But there are no documented cases of giardiasis being contracted from such low levels.8 Volunteer studies have shown that 10 or more are required to have a reasonable probability of it, with about one-third of persons ingesting 10 – 25 cysts getting detectable cysts in their stools.9, 10, 11, 13, [41], [42]

But be careful with statistics: Animal droppings containing 100,000 Giardia cysts deposited at the edge of a 10 million liter lake may be an average of only 0.01 per liter for the lake as a whole, but in the immediate vicinity of the deposit, the concentration can be much greater.

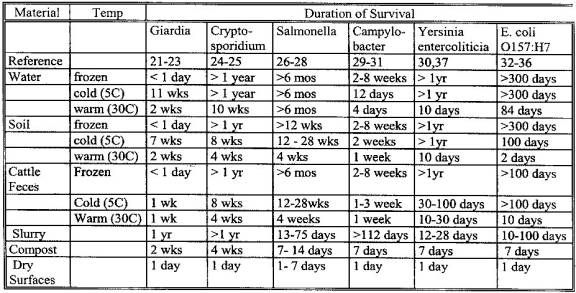

Table 2. Survival of Animal Fecal Pathogens in the Environment16

A comforting observation is that significant cyst inactivation, as high as 99.9 percent, can occur as a result of anaerobic digestion in sewage sludge.[43] Using a simple cat hole is not exactly a good approximation to the sewage plant process, but this points out the wisdom of burying it. On the other hand, cysts perish in a day or less on dry surfaces or when frozen,15, 16 so leaving it exposed to air makes some sense when burial is not feasible—especially when below-freezing temperatures are expected.

Since cysts that “winter over” in the Sierra Nevada are either in liquid water for considerably more than 2 to 3 months, or exposed to freezing temperatures, few—if any—survive the harsh Sierra winters. So, except for pollution by winter visitors and non-hibernating animals, Giardia contamination in the high country must begin essentially anew each spring.

The viability of Giardia cysts found in water is commonly assumed to be high, but monitoring experiments suggest otherwise. Subsequent to a drinking water outbreak in Ontario, Canada, in 1994, approximately half of the cysts found were dead.[44]

More good news: If you get a Giardia infection, you are unlikely to have symptoms 2, 9, 10, 21, 22, [45], [46]

The symptoms of giardiasis vary widely. Characteristic symptoms, when they occur, are mild to moderate abdominal discomfort, abdominal distention due to increased intestinal gas, sulfurous or “rotten egg” burps, horrific flatulence, and mild to moderate diarrhea. Stools are soft (but not liquid), bulky, and foul smelling. They have been described as greasy and frothy, and they float on the surface of water. Nausea, weakness, and loss of appetite may occur, but fever is uncommon. Studies have shown that giardiasis can be suspected when the illness lasts seven or more days with at least two of the above symptoms.10

However, most infected individuals have no symptoms at all. In a 1977 incident carefully studied by the CDC, disruption in the Berlin, New Hampshire’s water disinfection system allowed the entire population to consume water heavily contaminated with Giardia. Yet only 11 percent of the exposed population developed symptoms even though 46 percent had organisms in their stools. These figures suggest that (a) even when ingesting large amounts of the parasite, the chance of contracting giardiasis is less than 1 in 2, and (b) if you are one of the unlucky ones to contract it, the chance of having symptoms is less than 1 in 4. But perhaps the most useful statistic is that drinking heavily contaminated water resulted in symptoms of giardiasis in only 1 case in 9.2, 8, [47]

If you have symptoms it may not be giardiasis 2, 10, 19, 22, [48]

Many people claim that they “got it” on a particular trip into the wilderness. Yet, upon questioning, they usually report that the presence of Giardia was not confirmed in the laboratory. (Only 8 percent of persons with a diarrheal illness in this country seek medical care.31) Depending on the situation, other likely offenders are Campylobacter, Cryptosporidium, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Aeromonas, Clostridia, and some strains of Escherichia coli, with the last being the most common cause of traveler’s diarrhea worldwide. Food poisoning is also a possibility.

Cryptosporidiosis, in particular, is a growing problem in this country and, currently, there is no effective treatment for it. An outbreak in Milwaukee in 1993 caused 403,000 people to become ill and 100 to die. A year later, 43 people in Las Vegas died from the same disease.29

The severity of cryptosporidiosis depends on the condition of the host’s immune system. In immunologically normal people, symptoms and duration are similar to those of giardiasis. But in persons whose immune systems have been compromised (e.g., AIDS victims), symptoms can be profound: Frequent (up to 25), voluminous (up to 25 liters) daily bowel movements, serious weight loss, and cyst shedding often persist for months.

The diarrhea being blamed on Giardia from that Sierra trip a week ago may instead be due to some spoiled food eaten last night or Campylobacter in undercooked chicken four days ago. Or, because the incubation period is usually from one to four weeks, even if it is giardiasis the uncertainty range indicates that the perpetrators could have been ingested anytime during a full three-weeks worth of meals and beverages. People in high-risk groups for Giardia, such as family members of children in day care centers or promiscuous male homosexuals, have even more possible sources to consider. To indict a particular wilderness stream or lake under such circumstances, without being able to at least verify that cysts are indeed there at all, is illogical at best.

The type of diarrhea can help in the diagnosis: If it is liquid and mixes readily with water rather than floating on top, and is not particularly foul smelling, the problem is likely something other than giardiasis. Diarrhea that lasts less than a week, untreated, is probably not from giardiasis.

Almost always, giardiasis goes away without treatment 2, 9, 10, 19, 20, 21, 45, [49], [50]

If you are unlucky enough to get giardiasis with symptoms, the symptoms will probably be gone in a week or so without treatment. You may still be harboring the cysts, however, and can unknowingly spread the disease. Thus, practicing commonly recommended wilderness sanitary habits—defecating 100 feet from water, burying or packing out feces and toilet paper, washing before handling food, etc.—is an excellent idea.

Looking for cysts and trophozoites in stool specimens under the microscopic has been the traditional method for diagnosing giardiasis, but it is notoriously unreliable. Now, however, an immunologic test (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or ELISA) for the detection of Giardia antigens in stool samples is available. The antigens are present only if there is a Giardia infection. ELISA is a big improvement over the microscopic search, with detection sensitivities of 90 percent or more.

Rare individuals not only do not spontaneously rid themselves of the organisms, but instead develop serious symptoms of malabsorption, weight loss, ulcer-like stomach pain, and other chronic disturbances. Fortunately, this occurs in less than 1 percent of those with infestations. These unlucky people need medical treatment.

Metronidazole (Flagyl) has been the standard medication, with about a 92 percent cure rate. Recommended by the CDC, it is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for giardiasis because it can have some serious side effects and is potentially carcinogenic. Quinacrine (Atabrine) and furazolidone (Furoxone) are also prescribed. Tinidazole (Tinebah) is highly effective in single doses and is widely used throughout the world, but it is not available in the US; it can be purchased over-the-counter in many developing countries.10, 31

The problem may not be whether you are infected with the parasite but how harmoniously you both can live together. And how to get rid of the parasite when the harmony does not exist or is lost.9

The FDA, observing that giardiasis is more prevalent in children than adults, has long suggested that many individuals seem to have a lasting immunity after infection.[52] Furthermore, citizens of cities and countries where the parasite is numerous have few if any problems with their own water, which also points to acquired immunity.

If immunity can be acquired, might a vaccine be developed to counter Giardia? The subject has been explored successfully, and such a vaccine is now commercially available for dogs and cats.14, [53] Effective agents for the vaccine have been prepared from antigens on the surface of trophozoites, as well as from whole trophozoites themselves. Human response to these antigens has been studied and found promising.[54]

Giardiasis has been called a disease of “somes.” Some people do not contract it even from heavily contaminated sources. Some infestations vanish with no treatment at all. Some people become asymptomatic carriers. There is some evidence that some people acquire a natural immunity to some strains. And some strains seem more virulent than others.16, 19

So…what about the Sierra Nevada? 2, 9, 10, 11, 20, 22

In 1984, the US Geological Survey, in cooperation with the California Department of Public Health, examined water at 69 Sierra Nevada stream sites that were selected in consultation with Park Service and National Forest managers.[55], [56] Forty-two of the stream sites were considered “high-use” (high probability of human fecal contamination), and 27 were “low-use.” Cysts were found at only 18 (43 percent) of the high-use sites and at 5 (19 percent) of the low-use sites. The highest concentration of Giardia cysts was 0.108 per liter of water in Susie Lake, south of Lake Tahoe. The next highest was 0.037 per liter near Long Lake, southwest of Bishop. Samples taken in the Mt. Whitney area varied from 0 (most sites) to 0.013 (Lone Pine Creek at Trail Camp) per liter. The concentration was 0.003 per liter in Lone Pine Creek at Whitney Portal.

Recall that San Francisco water can contain a concentration approaching 0.12 cysts per liter, a figure now seen to be higher than that measured anywhere in the Sierra. San Francisco city officials go to great lengths to assure their citizens that the water is safe to drink and, if true—as it most assuredly must be—this comparison is quite revealing.

If San Francisco water is reasonably pure, Los Angeles Aqueduct water is even more so, with only 0.03 cysts per liter.36 But 0.03 cysts per liter is a higher concentration of Giardia than all but two of the 69 Sierra sites examined in 1984. Los Angeles Aqueduct water is collected from the streams of the eastern slopes of the Sierra: the very streams some people worry about when visiting those wilderness areas. It is interesting to conjecture how individual water sources in the eastern High Sierra can be seriously contaminated, if those sources are at the same time providing almost perfectly pure water for the aqueduct.

Taking the highest concentration measured in the Sierra (0.108), we can make some calculations. The probability[iv] of finding 10 or more cysts in a liter of water—to have at least a one-third chance of contracting giardiasis—is about 10-17. Ten cysts in 10 liters of water, about 10-7. In fact, one would have to drink over 89 liters to have a 50 percent probability of ingesting 10 or more cysts.

A word of caution: 1984 was quite a while ago, and areas of the Sierra may be differently contaminated now: some perhaps more and some perhaps less, depending on visitor population statistics.

Another reason for caution: A cyst does not just materialize, here and there, now and then. It was deposited by a mammal at a specific location in the space of a few seconds, along with many of its companions. They were then dispersed by the dynamic actions of water and wind, with some being killed by freezing, drying or aging, to eventually reach these low concentrations. The person, who fills his canteen too close to that location and too soon after the deposit, is unlucky indeed. Fortunately, the fact that people rarely contract giardiasis after wilderness visits means that this is not at all common. Later, some tips on “drinking smart” will be given to further reduce this already-minuscule problem.

And another: While so much attention is being given to Giardia, there are more serious organisms to worry about such as Campylobacter, Cryptosporidia, E. coli and the others mentioned earlier. But are these likely to be found either? While it is easy to conjecture about such organisms in High Sierra water, and many people do, searching for evidence of it is fruitless. Each year the CDC documents many disease outbreaks involving recreational water, but almost all occur from swimming pools, hot tubs and water parks. Some do occur from lakes, streams and rivers, but these are all at elevations of a few thousand feet or lower. If people are contracting these diseases from water sources like the High Sierra, or measuring contaminants in them, they certainly aren’t reporting it (see, for example, References 28 and 29).

A valid claim that giardiasis (or any disease) was contracted from a specific water source requires affirmative answers to each of the following questions: (1) Was the presence of Giardia confirmed in the laboratory? (2) Was the person Giardia-free prior to drinking it? (3) Did the suspect water source contain Giardia cysts in sufficient numbers to cause the disease? The answer to question (1) is easily obtained, and that to question (2) can usually, but not always, be presumed. In the case of wilderness water, however, the answer to question (3) is virtually never pursued.

In an informative study, investigators contacted thousands of visitors to one of the high-use sites during the summers of 1988 through 1990. Water samples taken on 10 different dates at each of three locations exhibited Giardia cyst concentrations between 0 and 0.062 (average 0.009) per liter. A goal was to enlist volunteers who were cyst-negative before their trip, verified by stool analysis, and later determine what fraction were cyst carriers after the trip. Unfortunately, stool collection is not a particularly enjoyable task, and only 41 people agreed to participate. Of these, two acquired Giardia cysts during their trip, but neither came down with symptoms. Six of the others exhibited post-visit intestinal symptoms, but none tested positive for Giardia (interestingly, all six had filtered their water). In sum, no cases of laboratory-confirmed symptomatic giardiasis were found.[57]

Beyond the Sierra

Outside of the Sierra, Giardia cysts in concentrations “as high as four per gallon” [v] have been detected in untreated water in northeastern and western states.[58] But, even with this concentration, one would have to consume over nine liters of water to have a 50 percent chance of ingesting 10 or more cysts.

Indeed, there may be as much unwarranted hysteria surrounding Giardia in wilderness water in these other areas as there is for the Sierra. For example, an oft-cited report describing acquisition of the disease by 65 percent of a group of students hiking in the Uinta Mountains of Utah[59] is now viewed with considerable skepticism. Specifically, the attack rate of 65% was far beyond that usually seen with water-contracted giardiasis, no cysts were identified in the suspect water, there was no association between water consumption rates and the likelihood of the disease, and the authors categorically discounted food-borne or fecal-oral spread, stating that it had never been reported (which was correct at the time).>3

Summary figures

Here are some of the figures discussed in various places above. Units are cysts per liter.

Table 3. Giardia Cyst Concentrations Discussed in This Report

If not from the water, from where?

The water that wilderness travelers are apt to drink, assuming that they use a little care, seems almost universally safe as far as Giardia is concerned. The study referred to earlier,3 in which the researchers concluded that the risk of contracting giardiasis in the wilderness is similar to that of a shark attack, is telling. What they did find is that Giardia and other intestinal bugs are for the most part spread by direct fecal-oral or food-borne transmission, not by contaminated drinking water. Since personal hygiene often takes a backseat when camping, the possibility of contracting giardiasis from someone in your own party—someone who is asymptomatic, probably—is real. Recalling that up to 7 percent of Americans, or up to 1 in 14, are infected, it is not surprising that wilderness visitors can indeed come home with a case of giardiasis, contracted not from the water…but from one of their friends.

This theme, that reduced attention to personal hygiene is an important factor for contracting giardiasis in the wilderness, is becoming more frequent in the literature.3, 13, 20, 57, [60]

Personal observations

I started visiting the Sierra Nevada in the early 1950s and have spent much of my free time there. I have never treated the water, and I have never had symptoms of giardiasis as a consequence of my visits. My many similarly active friends and acquaintances also drink the water, in the High Sierra and elsewhere, with no ill effects. But we are always careful to “drink smart”:

If in doubt, treat it—but how? While useful in many instances, chlorine is not very effective for Giardia disinfection, which is why swimming pools are primary sources for the disease. The best filters work, although they are costly, heavy, and bulky, and many are somewhat awkward to use.11, [61]

Boiling is usually inconvenient, but if you are preparing hot water for meals anyway, you may as well take advantage. Giardia cysts are highly susceptible to heat, and simply bringing water to 150° F. for five minutes, 176° for a minute, or 190° momentarily, will kill them.11, 13 But boiling for a few minutes is usually recommended because of the other organisms that may be present. At 10,000 feet elevation, water boils at 194°; at 14,000 feet, 187°; so longer boiling times are recommended at altitude.

Iodine is perhaps the best treatment choice, being inexpensive, convenient, and safe. Iodine is effective against most bacteria and viruses, too—and over a wide range of temperatures. But Cryptosporidium may be resistant to iodine. A popular system uses iodine crystals in a saturated water solution. Methods exist to mask or remove the iodine taste.

Does it matter what the organism is, if you are going to treat the water anyway? Filters effective for Giardia (a protozoan) are not always effective for Campylobacter (a bacterium). Chlorine may work against Campylobacter, but most of the time is ineffective against Giardia. You need to know your enemy.

Advice for visitors

On the subject of drinking water safety in the Sierra Nevada, we are told, “An intestinal disorder called giardiasis may be contracted from drinking untreated ‘natural’ water. This disorder is caused by a microscopic organism, Giardia lamblia, the cystic form of which is often found in mountain streams and lakes. Such waters may look, smell and taste good, but you should be aware of possible danger.”[62] We are instructed to filter or boil all drinking water.62, [63]

Many people make the leap to a belief, approaching paranoia, that every water source is seriously contaminated. I have seen day hikers to Mt. Whitney carrying 3 gallons of water from the grocery store. I have seen people filtering water for washing their dishes. If their filter breaks down on a hike, some will endure thirst in their rush to camp to boil water, passing pristine streams along the way. They do not trust fresh snow, and they certainly do not trust the trickles coming from it.

In 2001 I wrote to the Inyo National Forest office, asking for evidence that the water quality could be as questionable as they suggest. The Forest Supervisor wrote back: “As to whether or not Giardia exists in the Sierra, we are not in a position to state a fact one way or the other.”[64] This is a significant admission. So why do they persist in informing everyone that giardiasis is a potential hazard when visiting the Sierra Nevada?

First: They know that some waters can be contaminated by something, and Giardia is the organism on people’s minds so needs no elaboration. Contaminated water, with Giardia or otherwise, is certainly possible at lower elevations and in some locales. Noting that novice hikers in particular cannot be expected to make correct choices of which sources may be safe to drink, they suggest treating all water.

Second: If a person believes, albeit incorrectly, that they contracted giardiasis from Sierra Nevada water, they cannot claim they weren’t informed. Potential confrontations are therefore avoided.

Third: It is the CDC’s Division of Parasitic Diseases that advises the national park and forest managers in devising and revising those agencies’ warnings and recommendations.8 It is not surprising that this office would take a very conservative stance.

Unfortunately, the result is an incorrect perception of overall water quality in the Sierra by the general public, tainting the image of this pristine wilderness. It also means that if someone contracts a gastrointestinal illness after a visit, they will be more apt to blame the water, having been “forewarned” that all water is suspect. And so the egregious myth is perpetuated.

But what do rangers say off the record, and what practices do they themselves follow? Here are three data points:

Untreated Sierra Nevada water is, almost everywhere, safe to drink—if you “drink smart.” If you don’t “drink smart” you may ingest diarrhea-causing organisms. But they almost certainly won’t be Giardia.

Still, because up to 1 in 14 of us carries the Giardia parasite, we all need to do what we can to keep the water pure. Defecate away from water, and bury it or carry it out.

Camp cooks in particular need to pay special attention to cleanliness. Wash hands thoroughly, especially before handling utensils and preparing meals.

In summary: High Sierra water has too few Giardia cysts to pose a genuine risk. Even if you drink water elsewhere where the concentration is high, you probably won’t get giardiasis. If you do get giardiasis, you probably won’t have any symptoms. If you have symptoms, they will probably go away by themselves in a week or so. If they don’t or you develop serious persistent symptoms, you should seek medical treatment. Finally, those contracting giardiasis may develop immunity to it, thus lowering the likelihood that they will get it again.

There is certainly no reason for anxiety about giardiasis. Less than 1 percent of those who have an infestation, or about 5 percent of those with symptoms, needs medical help.

Closing thoughts

Wilderness managers are in a position to educate the outdoor public about the real culprit in the Giardia lamblia story: inadequate human hygiene. When they acknowledge that Sierra Nevada water has fewer Giardia cysts than, for example, the municipal water supply of the city of San Francisco, maybe they will turn their attention to it. The thrust of the following observation is long overdue:

“Given the casual approach to personal hygiene that characterizes most backpacking treks, hand washing is likely to be a much more useful preventative strategy (for Giardia) than water disinfection![viii] This simple expedient, strictly enforced in health care, child care, and food service settings, is rarely mentioned in wilderness education materials.”3

We are cautioned, “Wilderness water might be contaminated, so you should always treat it.” Given the well-documented instances when municipal water treatment systems have failed or been contaminated, the same warning could apply to drinking water—with much more validity. But the government does not say, “Drinking water might be contaminated, so you should always treat it.” Nor should they. We fill our glass from the tap without concern, well aware that on rare occasions our confidence is breached. We accept the minuscule risk.

Yet a few Giardia cysts are found in some wilderness waters, with no evidence that it is even remotely a problem, and an all-encompassing warning is issued.

How much more useful, candid and factual information would be!

About the author

The author is an active mountaineer who made his first trip into the Sierra Nevada in 1952 to climb Mt. Whitney, and he repeats this climb several times annually. He has a bachelor’s degree in Physics from UC-Berkeley, and a PhD in Aeronautical and Astronautical Engineering from Stanford University. In the course of making well over a thousand ascents of hundreds of individual Sierra Nevada mountains, he has never filtered or otherwise treated the water, and he has never contracted symptoms of giardiasis. Retired since 1990, he is now able to fully indulge in his favorite pastime and spends more time up there, drinking freely out of the lakes and streams, than ever before.

[i] Examples: http://www.yosemite.org/naturenotes/Giardia.htm, http://peakclimbing.org/articles/giardia.asp, http://highadventure.sdicbsa.org/wisdom.htm.

[ii] When a reference number appears after the title of a section, such as here, that reference has been used repeatedly within the section. When a reference number appears embedded in a section, information from that reference has been used for that specific statement or concept.

[iii] The referenced sources use a variety of units for portraying cyst concentration: cysts per 100 liters, per 100 gallons, etc. For uniformity, all have been converted to cysts per liter.

[iv] These calculations involve use of a mathematical tool called the Poisson distribution.

[v] Quoted from the original.

[vi] If one liter is consumed.

[vii] “In rivers, the water that you touch is the last of what has passed and the first of that which comes; so with present time.”—Leonardo da Vinci

[viii] Emphasis is in the original.

References

[1] Erlandsen, S. L. et al: Investigation into the Life Cycle of Giardia Using Videomicroscopy and Field Emission SEM. In Giardia, The Cosmopolitan Parasite, edited by B. E. Olson, M. E. Olson and P. M. Wallis. CABI Publishing, 2002

[2] Wilkerson, James A.: Medicine for Mountaineering and Other Wilderness Activities. The Mountaineers, 4th edition, 1992

[3] Welch, Thomas R. and Welch, Timothy P.: Giardiasis as a Threat to Backpackers in the United States: A Survey of State Health Departments. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine, Vol. 6, 1995

[4] Rockwell, Bob: Giardiasis: Let’s Be Rational About It. Summit Magazine, Nov./Dec. 1987

[5] Rockwell, Bob: Giardia Lamblia and Giardiasis, with Implications for Sierra Nevada Visitors. California Mountaineering Club Newsletter, Vol. 7 no. 2, April 1996

[6] Rockwell, Bob: Giardia Update. California Mountaineering Club Newsletter, Vol. 8 no. 2, April 1997

[7] Rockwell, Robert L.: Giardia Lamblia and Giardiasis, With Particular Attention to the Sierra Nevada. Unpublished note, 18 October 2001

[8] Thompson, Kalee: Water Wary? Your Backcountry H2O May be Safer Than You Think. National Geographic Adventure, June/July 2002

[9] Juranek, Dennis D.: Giardiasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1990

[10] Swartz, Morton N.: Intestinal Protozoan Infections. Scientific American Medicine, 1994

[11] Kerasote, Ted: Great Outdoors; Drops to Drink. Audubon, July 1986

[12] EOA, Inc.: Microbial Risk Assessment for Reclaimed Water. Final Report. Prepared in Association with the University of California School of Public Health, Oakland, CA. May 1995

[13] Backer, Howard D.: Giardiasis: An Elusive Cause of Gastrointestinal Distress. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, Vol. 28 no. 7, July 2000

[14] Thompson, R. C. A.: Towards a Better Understanding of Host Specificity and the Transmission of Giardia: the Impact of Molecular Epidemiology. In Giardia, The Cosmopolitan Parasite, edited by B. E. Olson, M. E. Olson and P. M. Wallis. CABI Publishing, 2002.

[15] DeReigner D. P., et al: Viability of Giardia Cysts Suspended in Lake, River, and Tap Water. Applied Environmental Microbiology, Vol. 55 no. 5, 1989

[16] Olson, M. E: Human and Animal Pathogens in Manure. Conference on Livestock Options for the Future. Winnepeg, Manitoba, June 2001

[17] Olsen, M. E., et al: Survival of Giardia Cysts and Cryptosporidium Oocysts in Water, Soil and Cattle Feces. American Association of Veterinary Parasitologists, 43rd Annual Meeting, 1998

[18]National Food Processors Institute: Fact Sheet on Enteric Protozoa and the Food Industry. October 1998.

[19] Moser, Penny Ward: Danger in Diaperland. Health, September/October 1991

[20] Suk, Thomas: Eat, Drink and Be Wary. California Wilderness Coalition

[21] Berkow, Robert, MD, Editor: Parasitic Infections—Giardiasis. The Merck Manual, 14th edition, 1997

[22] Wilkerson, James and Caulfield, Page: Wilderness Water Disinfection. Appalachia, No. 4, Winter 1985-86

[23] Bemrick, W. J.: Some Perspectives on the Transmission of Giardiasis. Giardia and Giardiasis: Biology, Pathogenesis and Epidemiology, edited by Erlandsen and Meyer, Plenum Press, 1984

[24] Feachem, R. G., et al: Sanitation and Disease: Health Aspects of Excreta and Wastewater Management. John Wiley and Sons, 1983

[25]State of California Department of Public Health: Communicable Diseases in California, 1994, 1995.

[26] Erlandsen, S. L. and Bemrick, W. J.: Waterborne Giardiasis: Sources of Giardia Cysts and Evidence Pertaining to their Implication in Human Infection. In Advances in Giardia Research, edited by P. M. Wallis and B. R. Hammond. University of Calgary Press, 1988.

[27] Vitusis, Ziegfried, chief microbiologist at the EPA. Quoted in Backpacker, Dec. 1996

[28] Lee, S. H. et al: Surveillance for Waterborne-Disease Outbreaks—United States, 1999-2000. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, November 22, 2002

[29] Kramer, Michael H. et al: Surveillance for Water-Borne Disease Outbreaks—United States, 1993-1994. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1996

[30] Kappus KD, Lundgren RG and Juranek DD: Intestinal Parasitism in the United States: Update on a Continuing Problem. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Vol. 60 no. 6, 1994

[31] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Giardiasis Surveillance—United States, 1992—1997. August 2000.

[32] Pickering, L. K. et al: Occurrence of Giardia lamblia in Children in Day Care Centers. Journal of Pediatrics, Vol. 104, 1984

[33] Porter, J. D. et al: Giardia Transmission in a Swimming Pool. American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 78 no. 6, 1988

[34]Stanford Utilities Division and San Francisco Public Utilities Commission: 2000 Annual Water Quality Report.

[35] City of Fairfield, California: 2001 Water Quality Report.

[36] Los Angeles Department of Water and Power: Annual Water Quality Report for 2000.

[37] Bean, N. H., PhD et al: Foodborne Disease Outbreaks, 5-year Summary, 1983 – 1987. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, March 1990

[38] Osterholm, M. T. et al: An Outbreak of Foodborne Giardiasis. The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 304, 1981

[39] University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources: Giardia and Cryptosporidium Levels are Low in Sierra Nevada Pack Stock. News Tips, December 1999

[40] O’Handley, R. M.: Giardia in Farm Animals. In Giardia, The Cosmopolitan Parasite, edited by B. E. Olson, M. E. Olson and P. M. Wallis. CABI Publishing, 2002

[41] Ortega, Y.R. et al: Giardia: Overview and update. Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 25, 1997

[42] Rendtorff, R: The Experimental Transmission of Human Intestinal Protozoan Parasites. American Journal of Hygiene, Vol. 59, 1954

[43] Cravaghan, P. D., et al: Inactivation of Giardia by Anaerobic Digestion of Sludge. Water Science Technology, Vol. 27, 1993

[44] Wallis, P. M. et al: Risk Assessment for Waterborne Giardiasis and Cryptosporidiosis in Canada. Unpublished report to Health Canada, 1995

[45] Mayo Clinic Family Health Book. Mayo Clinic Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 1996

[46] Tintinalli, J. et al, editors: Parasites: Giardia Lamblia. Emergency Medicine, 3rd edition, 1995

[47] Lippy, E. C.: Tracing a Giardiasis Outbreak at Berlin, New Hampshire. Journal of the American Waterworks Association, Vol. 70, 1978

[48] Soave, Rosemary: Cryptosporidiosis. Textbook of Medicine, edited by James B. Wyngaarden et al, 1991

[49] Peter, G., MD, editor: Chapter 3: Summaries of Infectious Diseases. American Academy of Pediatrics. 1994 Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases

[50] Heyworth, M. F.: Immunology of Giardia Infections. In Advances in Giardia Research, edited by P. M. Wallis and B. R. Hammond. University of Calgary Press, 1988.

[51] Olson, M. E. et all: Giardia Immunoprophylaxis and Immunotherapy. In Giardia, The Cosmopolitan Parasite, edited by B. E. Olson, M. E. Olson and P. M. Wallis. CABI Publishing, 2002.

[52] US Food & Drug Administration: The Bad Bug Book. Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition, 2001.

[53] Olson, M. E. and Morck, D. W.: Giardia Vaccination. Parasitology Today, Vol. 16, No. 5, 2000

[54] Ortega, M. G.: The Response of Humans to Antigens of Giardia lamblia. In Advances in Giardia Research, edited by P. M. Wallis and B. R. Hammond. University of Calgary Press, 1988.

[55] Dept. of the Interior, US Geological Survey: Open File Report No. 86-404-W. 1986

[56] Suk, T. J. et al: The Relation between Human Presence and Occurrence of Giardia Cysts in Streams in the Sierra Nevada, California. Journal of Freshwater Ecology, Vol. 4, No. 1, June 1987

[57] Zell, S. C. and Sorenson, S. K.: Cyst Acquisition Rate for Giardia Lamblia in Backcountry Travelers to Desolation Wilderness, Lake Tahoe. Journal of Wilderness Medicine, No. 4, 1993

[58] Ongerth, J. E. et al: Backcountry Water Treatment to Prevent Giardiasis. American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 79 no. 12, 1989

[59] Barbour, A. G. et al: An Outbreak of Giardiasis in a Group of Campers. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, Vol. 25, 1976

[60] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Giardiasis Fact Sheet. May 2001

[61] Gorman, Stephen: Mountaincraft: Water Treatment. Summit Magazine, Fall 1993

[62] Inyo National Forest web site: http://www.fs.usda.gov/detailfull/inyo/learning/safety-ethics/?cid=FSBDEV3_003828&width=full#purification.

[63] US Forest Service: Wilderness Ethics and Etiquette. Inyo, Sierra and Sequoia National Forests. Brochure handed out with 2003 wilderness permits. 1994 (rev. 5/95)

[64] Bailey, Jeffrey E., Forest Supervisor, Inyo National Forest. Official correspondence, File Code 2320, November 19, 2001

[65] Informal discussion. Eastern Sierra Mountainfest. Bishop, California, October 25, 2002

[66] Durkee, George, Sequoia National Park Backcountry Ranger. Personal correspondence, January 30, 2002