Search and Rescue Dogs are a vital part of many operations. This page is dedicated to Trapper who was a faithful member of our team. He and his handler, Sallee Burns, have our thanks for many hours training and searching.

SAR dogs can do a lot of amazing things, including rappel down mountainsides with their handler, locate a human being within a 500-meter radius, find a dead body under water, climb ladders and walk across an unstable beam in a collapsed building, but it's all toward a single end: Finding human scent.

Ursa and handler Noreen McClintock practice rappel

This may be in the form of a living person, a dead body, a human tooth or an article of clothing. SAR dogs find missing persons, search disaster areas for survivors and bodies and locate evidence at crime scenes, all by focusing on the smell of a human being.

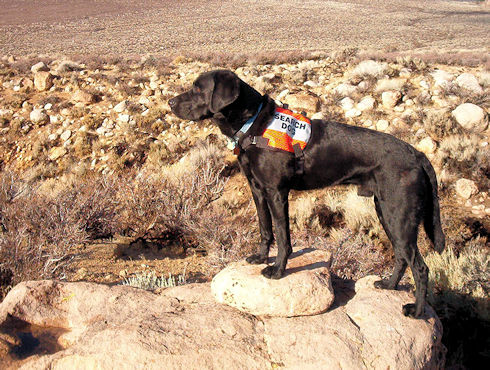

While SAR dogs are valuable in urban situations, this discussion focuses on "wilderness" SAR dogs. These dogs find lost or injured people in a wilderness, rural, or undeveloped suburban property setting such as the Eastern Sierra.

Experts estimate that a single SAR dog can accomplish the work of 20 to 30 human searchers. It's not just about smell, either -- dogs' superior hearing and night vision also come into play. Time is always an issue in search and rescue.

In an avalanche situation, for instance, approximately 90 percent of victims are alive 15 minutes after burial; 35 minutes after burial, only 30 percent of victims are alive. While most avalanche victims don't survive, their chances increase exponentially when dogs are in on the search. Even in cases where victims are presumed dead, dogs are invaluable assets -- they locate the bodies so family members can have closure and give their loved one a proper burial.

A good dog team can be one of the most valuable assets to a SAR operation. The proper place for a dog team is as an integrated part of an incident-command-system run SAR operation that makes full use of the strengths of many different resources.

Inca, a water trained dog, assisted with a search at June Lake - Lyon County Search & Rescue

Fielding Water Search Dog Teams

Search dogs can be a useful tool to complement and increase the efficiency of various search resources in water searches, reducing time and expense, and most significantly adding a margin of safety for other searchers.

There is no magic in what our canine partners do, although their unique abilities may at times appear so. An astute and resourceful search manager will utilize dogs as part of the search team, relying on their abilities to augment the strengths of other search methods.

Water searches are always tragedies, and the final outcome is never a joyous occasion as often occurs on missing person searches. The faster the situation can be resolved by locating the body, the easier the situation will be for the friends and family of the person who drowned.

For more infomation visit:

Training a Cadaver Water Search Dog

Canine Search & Rescue Water Search Training

Types of SAR dogs

Cadaver and water-search dogs are the only types specifically trained to scent for human remains, although all SAR dogs will alert to remains if they find them.

For information on SAR dog training standards, check How Search-and-rescue Dogs Work by Julia Layton at How Stuff Works

Humans are constantly losing "rafts" of dead skin cells. The larger rafts settle to the ground or other objects. Smaller and lighter rafts are carried away in the wind. Even the slightest draft will carry skin rafts. SAR dogs can smell these rafts.

There are two main types of SAR dog. The trailing (or tracking) dog follows the human scent trail on the ground. The air-scenting (or area) dog follows airborne scent directly to the search subject. (See also the side-bar).

Each type of dog has its strengths and weaknesses; each can play a crucial role in a successful search, if used properly. Some dogs are cross-trained in both specialties.

SAR dogs are usually owed and trained by their handlers. The initial training process can take 1-3 years.

Training continues once the dog team becomes "Mission Ready" (certified) to maintain proficiency and are retested semi-annually or annually depending on their discipline(s).

While some dogs exhibit a stronger desire to scent than others, every canine out there has a powerful sense of smell. SAR dogs may be purebreds or mutts.

Some handlers have a breed of choice, but any medium-to-large dog in good physical health, with decent intelligence, good listening skills, a non-aggressive personality and a strong play/prey drive (an intense, enduring desire to retrieve a toy) can potentially go into search and rescue.

Takoda and handler Christina Ackerman

SAR dogs need to be big enough to successfully navigate treacherous terrain and push debris out of the way and yet small enough to transport easily. You actually don't find too many Saint Bernard search dogs these days, because they can be cumbersome.

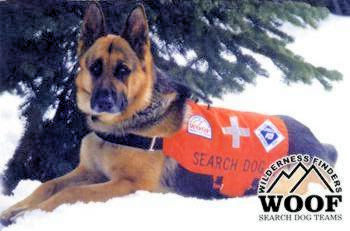

German shepherds are a popular SAR breed -- they're typically smart, obedient and agile, and their double-layered coat insulates against severe weather conditions. Hunting and herding dogs like Labrador and golden retrievers and border collies tend to be good at SAR work, too, because they have a very strong prey drive.

Many people consider bloodhounds to be the best breed for tracking -- their giant ears and facial folds serve to collect and concentrate scent particles right at their nostrils, making their sense of smell extremely powerful and discerning. A bloodhound can pick up a trail weeks after other breeds can't find it.

It's important to remember that humans invented the distinction between trailing and air-scenting. In fact, a trailing dog will air-scent if that's how the strongest scent is coming to her; and an air-scenting dog will follow a hot ground trail. But each dog is most reliable when performing the task that she's been specially trained to do, and handlers tailor their tactics in the field to take advantage of the dog's strengths.

Another, overlapping, type of specialty training exists: the cadaver dog. Scent can escape from water, earth, or even cracked or porous concrete. Dogs can thus be used to find human bodies that have sunk or been buried, as well as those on the surface. Many air-scenting and trailing dogs are cross-trained on human cadaver scent so that they can find human remains if they come across them.

Trailing Dogs

"Trailing" (or tracking) dogs are trained to find a live subject by following the path that a subject has traveled in a wilderness or urban environment. A Trailing Dog does this by the handler first obtaining an article, usually an article of clothing from the subject’s home or vehicle.

When at the last known location of the subject the handler introduces the scent article to the dog. At that point the dog will follow the path that the subject has traveled. Trailing dogs sometimes, but not always, work on leash with the handler trailing behind until the subject is found. Trailing dogs are most useful in wilderness searches.

Trailing dogs use the same skin rafts as the air-scent dog, but they mainly use the heavier rafts that stick to objects, i.e. the grass, low lying branches, etc., to follow the "trail" left behind by the person.

Bosley - Handler Dadre Albaugh

Most trailing dogs will also use the smaller, lighter skin rafts when they get close enough or there is a strong "scent pool" (A scent pool is any place that scent can linger in large quantities.)

As someone walks or runs, they leave footprints. A dog may not see them, but they sure can smell them. As each footprint is made, fresh soil is kicked up or moved and/or vegetation is crushed causing the "foot print" to smell different from the surrounding area.

Generally, a trailing dog begins working at the search subject's last known location -- called the point last seen (PLS) or last known point (LKP). From there, the trailing dog follows the ground scent left behind by that person, traveling more or less along that person's route of travel until either she finds him or loses the trail for some reason.

Trailing dogs must be trained to scent discriminate. When given a scent article that only the subject has touched, the dog can follow that person's trail -- even if it crosses trail scent left by other people.

Trailing dogs are a powerful SAR resource. If a ground trail is relatively fresh, if searchers have a good PLS or LKP, and if they can find an uncontaminated scent article, a good trailing dog can be the fastest, most direct way of getting to the subject.

But hand in hand with those strengths come corresponding weaknesses. While moisture and warmth are generally good (they help bacterial production of odor molecules, as we'll discuss later), rain and the passage of time can destroy a ground trail. So can ill-considered search efforts at the LKP -- a common mistake is to set up a command post on the LKP, thus destroying any chance of finding ground trails.

Often a scent article isn't available -- or just as bad, has been contaminated with other people's scent. In these cases, an uncritical reliance on the dog can lead to disappointment -- and in an unfair assessment of the dog's abilities. To minimize such contamination, scent articles should be handled as little as possible before being given to the dog.

A word of warning about scent discrimination: it is an extremely powerful technique, but only if done properly. Research studies have revealed that scent-discriminating dogs can be "skunked" if presented with a task that is sufficiently different from the problems they've trained on.

As with any other facet of SAR dog work, we're making use of dogs' innate abilities -- but we can't be sure we have the ability to direct and take advantage of those abilities unless we've trained under realistic conditions. Scent discrimination work should not be undertaken lightly, and must be done well if it's done at all.

Air-scenting dogs

"Air-scenting" (or area) dogs detect human scent on the wind. They tend to pick up scent coming directly from the search subject, and so may take a more direct route to the subject than a trailer would. But first the dog has to be downwind of the subject, and thereby hangs the tale.

Methodically "sampling" an area's smells as a dog team moves through it is one of the challenges of air-scenting dog handling. Because of the need for the dog to range unrestricted by the handler to find airborne scent plumes, air-scenting dogs work off-leash.

Early in a search, experienced SAR incident commanders generally will employ air-scenting dog teams for "hasty search" patterns, designed to get the "easy" find quickly and collect information for later in the search.

Late in a search, air-scent teams are useful for sweeping, or gridding, large areas.

Air-scent handlers generally don't do discrimination/trailing work with their dogs, instead letting the dogs find and report on any human who is in the area. In practice, this is not usually a drawback: anyone in the area is a potential witness with information about the search subject, and so needs to be interviewed. On the other hand, discrimination-trained air-scenting dogs can be a particularly flexible, useful SAR resource.

An air-scenting dog's lack of specificity can be a problem in a highly contaminated area. If a search area isn't cleared of hunters, hikers, or other searchers (the time necessary is highly dependent on local conditions), a dog team can waste a lot of time finding many wrong people, or even pockets of residual scent.

More experienced dogs, especially if they've done some training in semi-crowded park and suburban environments, have some ability to compensate for these problems.

An air-scenting dog can often detect and localize human scent from 100 yards or more. The longest such detection on record is two miles, set by a dog on the Alaskan tundra. But these results are highly dependent on weather conditions. Investigations in canine sweep width suggest dog probabilties of detection (PODs) at 100 yards ranging from about 80 percent or more on cloudy, windy days and clear nights, to 65 percent or less on still, sunny days.

It's important to remember that, while air-scenting dogs can and do find people, much like human searchers they more often find clues. A dog may catch a whiff of a person's scent that's too brief to follow -- but a watchful handler will notice this "alert," and search commanders can note the location of the alert and the wind direction on their maps.

Another search team, dog or human-based, can then check in that direction to see if the person is there. This level of dog team/command team integration is probably not realistic until both groups have worked with each other and become comfortable with each other's capabilities over time.

The clue value of reported dog alerts is highly variable, depending on the amount of human traffic in and adjacent to the search area, previous scent contamination, and perhaps most importantly, the experience level of the dog's handler.

Bosley and handler Dadre Albaugh

Bosley digs for victim

Scent and atmospheric conditions

The study of how weather affects scent is that of a lifetime. But dog handlers have learned a few simple tricks for making nature work for them -- or at least for preventing nature from completely disrupting their efforts.

At daybreak, both the air and the ground tend to be relatively cool. But sunrise makes two changes in this more-or-less stable situation: it serves as the engine for wind movement, and it heats the ground.

Sunlight passes right through the air without heating it much. But the sun does heat the ground relatively quickly. The result, early in the morning, is cool air over warm ground. The ground warms the air directly above it; once warmed, that air tends to rise past the still-cool air higher up.

Even in the absence of true wind, these "convection currents" will tend to produce a gentle uphill breeze. For this reason, early in the morning dog handlers like to be at the tops of hills or ridges, where their dogs can pick up any scent rising from the valleys below. Experienced SAR incident commanders will, therefore, try to task dogs before the sun starts warming the ground, so that they are in place to take full advantage of the updrafts when they begin.

Later in the day, especially sunny days, these uphill convection currents can get too strong. Warm air rising through cool air tends to be chopped into little pieces -- watch how the air seems to crinkle over hot pavement in the summer -- and any scent carried by that air gets chopped up as well.

Aside from the fact that it's difficult to keep a dog safely watered on a warm, sunny day, convection can often destroy air-scent so completely that a team of ground searchers would be able to do a better job than a dog. This can even happen on clear, sunny, but cold winter days.

Around sundown, though, this picture changes enormously. Now the air is thoroughly warmed. But just as the air doesn't gain heat easily, it doesn't lose heat easily either. The ground gives off heat in the form of infrared radiation, cooling quickly, and now we have warm air over cool ground.

Now the ground cools the air slowly, and the convection currents work in reverse, with air tending to sink downhill. This is a great time for dog searching: a dog at the bottom of a valley can get a good smell of the slopes on either side.

On clear nights, eventually much of the day's heat escapes into space, with the air and ground reaching equally cool temperatures. At this point -- called stable conditions by meteorologists -- scent travels with no loss to convection, and very long-range detection by scent is possible. For this reason, dogs are an extremely efficient resource for night searching.

Clouds trap heat and reflect it back to the ground, leading to intermediate conditions. While winds (the long-range movement of air with weather fronts, as opposed to convection currents) are generally good because they make scent move faster and farther, they cause other complications.

Wind can overwhelm convection currents; it can also combine with them to produce complicated spiraling air currents. Generally, air-scenting dog handlers try to get downwind of an area to work; but isolated convection cells or turbulent eddies can trap scent on the downwind side of buildings or sharp downhill slopes, making detection downwind difficult.

Rain can wash scent out of the air, forcing normally air-scenting dogs to keep their noses low or even washing out scent completely. Falling snow can also scavenge scent components from the air; its been found that dry, powdery snow is especially "scent sticky" and can magnify the effects of any scent contamination in the area.

The nature of scent

Human beings are messy. As we walk, we shed a continuous stream of gaseous molecules. In addition to gaseous molecules, people trail behind them microscopic flakes of dead skin. These "skin rafts" are tiny scent generators. The bacteria, perspiration, and skin secretions they carry generate more scent molecules with time.

As you can see, we are effectively leaving a "road map" for SAR dogs to follow. Trailing dogs are trained to follow this map.

The different components of the cloud of debris that we emanate act very differently. Larger flakes of dead skin tend to fall to the ground relatively quickly. They, and the scent molecules they continue to generate, become a trail of ground scent.

Other scent components -- smaller skin raft particles and gasses -- can travel indefinitely on the wind, becoming the air-scent. Some of the smelliest of human scent molecules are created when bacteria create carboxylic acids out of skin oils, and when the body releases "panic scents" -- steroid-like molecules produced by the apocrine glands, found in the armpits, groin, and in smaller numbers elsewhere on the skin.

Research in the 1980s and 1990s revealed that this combination of carboxylic acids and odiferous steroids seems to play a major role in the human body odor that humans can smell. Interestingly enough, these same chemicals have also been implicated in studies of how animals (mostly rodents) discriminate between other individual animals by scent. It is suspected that these substances are what SAR dogs smell when they're looking for people, but it hasn't been proved yet.

The Dogs are not the only "people" who need training. The "humans" also need training: Guidelines for Canine Field Team Members

Search and Rescue K-9s (PDF) - Mono County Sheriff's Search and Rescue Information

Working Dogs - Search and Rescue

Rescue Dogs Video from PBS KIDS

In the PBS KIDS video, Dr. Ben Ho trains dogs in search and rescue (SAR) techniques, and his "partner" is a German shepherd named Argus. Together, Ben and Argus work with Wilderness Finders Search and Rescue to find missing people, which has included lost hikers, natural disaster victims, or even survivors of the extreme 9/11 tragedy in New York City. Ben is one of the leading rescue workers in the nation and has been recognized for his work many times.

Slider - handler Sallee Burns

The following Mono County articles illustrate the value of Search and Rescue Dogs:

Check these pages for additional information about Search and Rescue Dogs:

Avalanche dog in training - Lisa Whatford, El Dorado SAR, playing with Lucy, a search dog from Calavares SAR

Lucy has found victim

Lucy pulls Lisa out of the hole

How Search and Rescue Dogs Work

How Search and Rescue Dogs Work