Searching for a lost person can involve many strategies depending on the probable location of the missing person, their age, weather, availability of air resources, and more. The following information will introduce you to these strategies.

Search Management Action Plan PDF

Chapter 4: The Search

This Chapter covers the following topics:

1. Fundamentals of Search Planning

2. Sign-in and Team Briefing

3. Search Considerations

4. Search Techniques

5. Finding and Handling Clues

6. Death Scene

7. Team Debriefing and Sign-out

8. Summary

1. FUNDAMENTALS OF SEARCH PLANNING

The search area is the geographic location presumed to contain the missing subject and in which search operations are located. During the planning for a search, the area is divided into segments based on information gathered from the initial and subsequent investigations and search team results.

Search Probabilities:

Each segment is assigned a Probability of Area (POA) – the estimated probability, expressed as a percentage, that the segment contains the subject. Each segment is sized suitably for a specific search resource, such as a hiking or snowmobile team.

When a team searches a segment, there is an estimated probability it would have found the subject if the segment actually contained the subject. This is known as the Probability of Detection (POD). The POD can depend on the:

Depending on your team’s kind, the Incident Management Team (IMT) may ask your team to estimate your POD based on how you carried out your search during the team’s debriefing. By practicing your search techniques in controlled exercises you can learn to estimate your POD. Studies have shown that most searchers, including experienced searchers under estimate the POD. POD may also be determined mathematically based on the searchers’ search width and time spent searching. POD is affected by the type of search conducted, the kind of search team, the environment and how long search teams are actively searching. If you have any interest in learning more about search theory, there are many on-line sources and written documents that cover the subject.

As searchers complete their respective assignments, the search managers need to consider the Probability of Success (POS). The POS is the probability that the subject will be located. By associating the POD with the POA in the equation POA X POD = POS, the search managers can determine the POS of the search segment.

As assignments are completed, the POA is adjusted by the derived POS for each searched area. The new POA will be used to plan future team assignments in that segment. This information could lead to areas being searched multiple times until the adjusted probability has been sufficiently reduced. Therefore, you might be asked to search a segment that has already been searched.

You may be asking; "Why do I need to know this stuff? I just want to go search." The answer is simple. As a searcher, you won’t be doing any of the calculations to determine the POA or the POS of a search segment. But, as a searcher, you do need to be aware of the importance of your POD from each of your search assignments. The POD is instrumental in assisting the search managers to allocate resources to accomplish the incident objectives.

2. SIGN-IN AND TEAM BRIEFING

When you arrive at Incident Base, sign-in on ICS Form 211 and include applicable information. This critical action is for your personal safety and allows the Incident Management Team (IMT) to manage the human resources on an incident.

Prior to your team starting its assignment, you will be briefed on the following:

If your team is equipped with one or more Global Positioning System units, you may be asked to track your route during your search.

This is the time to ask any questions you may have.

3. SEARCH CONSIDERATIONS

Identification of the search area

In the briefing for an area search, you will be given the boundaries of the segment you are to search. Search segments are chosen for specific reasons by the ICS Staff. They allocate search resources by estimating the probability that each segment contains the subject and the odds that a particular search technique will locate the subject if he or she is actually there. It is essential to the planning and execution of the mission that you carry out your assignment in the correct area and according to the briefing; do not deviate from the assignment without permission.

One of your team’s priorities is to identify your assigned segment and then make sure the segment is covered in the assigned manner and time allocated. This could mean marking the region with trail tape, Global Positioning System (GPS) waypoints, or even just marks on a paper map. Your team leader should determine the best spacing between searchers for route or grid searches that will effectively cover the assigned area within the time allocated. At the conclusion of the assignment, you must verify that you covered the assigned area and report any gaps in your coverage.

Marking the search area

In general, personnel move through the search segment in an organized line, marking the search site as they travel through it. For example, in the illustration below, there are three searchers moving through an area. Searcher 1 will walk a path parallel to some search area boundary, such as a trail, fence, drainage or simply a compass heading. Searchers 2 and 3 then place themselves within the assigned area some distance to the right of searcher 1. While moving from the bottom left of the search area, searcher 3 (the guide person) marks the path taken with streamers of trail tape. This searcher will also walk a straight bearing to keep the search within the desired bounds.

When the top boundary of the search segment is reached, the line reorganizes to the right, and begins to search from the top right down to the bottom right. Searcher 3 retraces the path taken on the first pass, retrieving the trail tape laid out before, while searcher 1 marks the path taken on the right. This process continues until the final pass, after which there should be no trail tape left in the area and the entire area has been searched. In larger teams the roles of guide person and marker might fall to other searchers.

By marking the area searched in this manner, your team can maintain a consistent direction through the search area and avoid large gaps in coverage.

It may be necessary to mark the top, bottom, and sides of the search area for future teams if the segment is not bounded by obvious physical boundaries like trails or fence lines. The markers can be either removed by later teams or biodegradable flagging tape can be used.

Efficiency vs. thoroughness

One choice to be made in selecting an area search technique is how thoroughly the area needs to be searched or covered. It is a mistake to cover an area thoroughly when you are asked to cover it quickly (or vice versa). If a subject is in a segment, you could have a high probability of a find if you searched the area in tight formation, shoulder-to-shoulder – but it is seldom wise to do so.

Search planners decide the thoroughness needed in a given segment. We should not assume that maximum thoroughness is either necessary or even desirable. Sometimes we need to sweep quickly through a low-probability region. It all comes back to the goal of the IMT needing to increase the overall probability of finding the subject quickly.

Average maximum detection range (AMDR)

An easily measured quantity often used in a grid search, the AMDR (also known as a Detection Range Experiment) is an estimate of the average distance beyond which searchers can no longer detect the object they’re looking for.

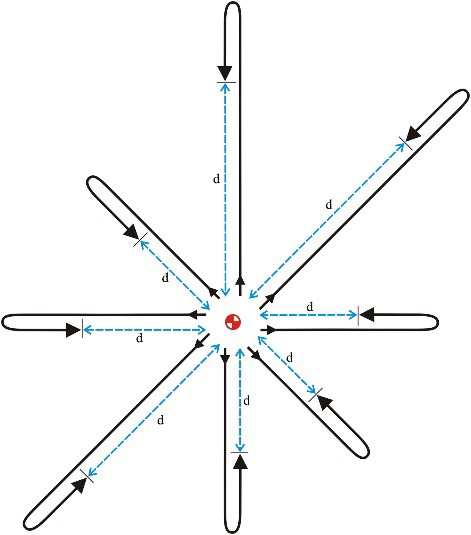

The measurement process is easy. An object the size, shape, and color of a possible clue is placed in terrain similar to that of the search area. Searchers first walk away from the object until it is no longer visible (this distance is known as the extinction distance). Searchers then walk towards the object until it can be seen again (the detection distance). The distance is measured by pacing. The searchers then move clockwise around the object and repeat the measurement every 45 degrees. The figure on the right shows how the experiment should be conducted. The average of the eight measured detection distances is the AMDR. It is a very rough measure of the detectability of the object in the search environment.

Effective Sweep Width

The Effective Sweep Width (ESW), also known as the Sweep Width (W) is a mathematically derived value that can assist search managers in determining the POD of a search team. The value is basically the distance to the left and right of a search team member, that a search team member may detect a specific object. The ESW is affected by many factors to include the terrain, environmental conditions, the search object, searcher speed and even the type of search sensor (K-9, naked eye, night vision goggles, etc). The ESW is normally based on extensive studies of searchers (sensors) moving through a specific area (terrain), at a consent speed, looking for specific type of object. Only after numerous studies are conducted and analyses of the data are completed, can the ESW can be determined for a particular search area.

Without the extensive studies, the ESW can be estimated by taking the AMDR and multiplying it by a factor of 1.1 for low visibility objects to 1.8 for high visibility objects. The visibility of the search object may be determined through the Incident Management Teams investigations. A subject wearing all hunter orange may be considered high visibility while a hunter in all green or black may be considered low visibility.

Search managers than can take the estimated ESW, apply it and other factors to a search team and determine what POD could be reached and, more importantly to the search team, obtain specific data from a search team’s debriefing and compute what POD was obtained by the team.

4. SEARCH TECHNIQUES

A progression of techniques is usually applied to a search. The two principal approaches of search strategies are passive (indirect) and active (direct).

Passive Search Approach

Passive Approach includes those tactics, strategies and considerations that gather information about the subject, confine the subject to a search area, determine if the subject has left the search area, causes the subject to move to a specific location or reveal the subjects location to searchers. They typically do not involve physically entering a search area to look for the subject or clues. Typical tactics of the passive approach are fact-finding/investigation, attraction, and containment/confinement.

Fact-finding/Investigation

Early in a SAR mission, the New Mexico State Police Mission Initiator (MI) and the Incident Commander (IC) are the primary users of these techniques. The investigator gathers information about the subject and reporting party, as well as information necessary to determine:

Continued investigation is critical throughout the mission to refine search plans or to possibly locate the subject outside of the search area (commonly called the "rest of the world" or ROW). For example, the subject may actually have made his way to an area hospital, home, or other location.

While investigation is a critical component of search operations, it is not a responsibility of field teams. As a field responder you should not conduct investigations unless you have been asked to do so, especially if the investigation involves speaking to the reporting party or to a member of the subject’s family.

During the course of a search you might, however, encounter hikers and other parties who might have helpful information. It is entirely appropriate for you to speak to these people and report any data back to Incident Base.

Attraction

These techniques attempt to catch the attention of the missing subject. Two common methods are sound and light attraction.

Using whistles, horns, loudspeakers, or even just your voice, you can periodically make noise and then pause to listen for any response. It is critical to observe a period of complete silence after the first noise is made. Talking, crunching of leaves or snow under foot, rustling of clothing, or the blaring of team radios can completely obscure any response from the subject. After the period of silence, the process is repeated once more. The second attempt allows for the possibility that the first noise alerted the subject to "something" and that the second noise will be properly recognized for what it is.

Remember, it could be very difficult for the subject to hear even your loudest noises over chattering teeth and/or when the hood of the subject’s jacket is pulled over his head!

Staff at Incident Base and those on containment/confinement assignments may also use light attraction. For example, they may shine bright lights in all directions in hope the subject may see them and walk toward them. A Law Enforcement Officer may also use flashing lights for attraction, as well as using the siren for sound attraction. There is also the technique of placing a battery-operated strobe light and a note at a trail intersection to attract the missing subject.

Positioning searchers in lookout towers, look-overs, scenic views, bridges and other high areas is another passive tactic that can assist searches in locating the subject. Personnel located at high points in or around the search area can continuously scan the search area with binoculars, night vision goggles, thermal imagers or by the naked eye to locate the lost subject. The high point itself can act as an attractant and attract the lost subject to its location.

Containment/Confinement

These techniques are designed to prevent the subject from leaving the search area undetected. Containment allows the search to be confined to a small area and improves the probability of locating the subject with limited resources and time.

Containment/confinement assignments include:

Containment/confinement assignments are crucial in the earlier stages of a search and should be maintained throughout the search mission. You might see these assignments as particularly unglamorous or mundane, but they are critically important. If we can be sure the subject has not left the search area, the opportunity for a find in the primary search area increases.

Active Search Approach:

Active tactics involve deploying search teams to conduct proactive searches in a region thought to contain the subject; the two key tactics are hasty and area searches.

Hasty Search

This refers to the rapid deployment of searchers to locations, or along routes, that are likely to contain the subject or clues of the subject’s passage. This technique is commonly used in the initial phase of a SAR mission.

The hasty search is not limited to the simple "clearing" of a trail by walking along it looking for the subject although this is certainly a common hasty search assignment. Typical assignments include:

Segment Search

After the initial deployment of hasty search personnel, it is often necessary to search larger areas as well as other routes and attractive features.

Segment searches are often referred to as grid or line searches, but does refer also to route searches and sound sweeps. A team of searchers is generally organized along a line. The team moves deliberately through their assigned segment looking for clues. In some cases a team may be asked to repeat a search in the same area, but at right angles to the original line.

A segment search is much more resource-intensive than a hasty search and is by necessity more destructive of clues.

Segment Search Tactics: Segment searches can be classified as route search, grid search (loose, tight or evidence), sound sweep and expanding circle – these each have different methods of deployment of searchers. Searchers need to attempt to keep their spacing uniform throughout the assignment during segment searches to insure a thorough coverage. Leaders should select search area boundaries, whether the boundary is natural, man-made, or set up, that are easily identifiable by the search team. During route search, searchers may be spaced apart to achieve an Effective Sweep Width, a value normally determined by the search managers from AMDR experiments. The number of searchers, speed of searchers, size of search area and terrain are just some of the variables used in the equations to determine the Effective Sweep Width that could produce a desired POD for the search segment.

Route Search: The most common segment search tactic used is where searchers follow a track parallel to a side boundary and maintain a predetermined separation. The search area may be covered in multiple passes and purposeful wandering (explained below) may be employed.

Grid Search: The grid search tactic is to be utilized when the POD needs to be raised and when looking for unresponsive subjects, to include evidence. Grid searchers are normally conducted with a line of searchers moving through an area with the searchers tightly spaced and following a compass bearing, attempting to travel as straight as possible to insure thorough coverage. Grid searches can be further described as loose, tight and evidence, depending on the searcher separation as determined by the AMDR or the effective search width to obtain a needed POD.

Loose grid search: Loose grid searches require less effort to cover large areas but have a lower probability of locating the subject or any clues. The size of loose grid teams is generally three to five searchers who are separated by more than twice the AMDR. They are spaced closely enough to see one another, but there may be areas between them that are not being searched effectively.

Loose grid techniques are typically used early in a search, especially when:

Tight grid search: A tight grid search focuses on thoroughness to achieve a high POD. Searchers move through the assigned area in parallel tracks of spacing less than 1 ½ times the AMDR. Tight grid search teams are usually larger than a loose grid team to keep the search time within reasonable limits.

By being closely spaced, searchers scan overlapping areas. Thus an object between them is less likely to be missed and the POD rises. Conversely, the area they cover in a single sweep is reduced, and the effort and time required to search the segment is increased.

A tight grid search is not always appropriate and is a "last resort" technique because:

That said, when a high-POD search is an operational necessity, a tight grid search is the tool of choice.

Evidence search: An evidence search is an especially thorough tight grid search designed to find everything that can be found. As such, this technique is usually used at a crime scene or suspected crime scene where finding every single clue is more important than the time taken to find them. It is often used when the subject is known to be deceased and where time is no longer a factor.

Expanding Circle: This tactic is only effective for a small area and is primarily used around the Initial Planning Point (IPP). It is conducted by starting the search at the IPP or where a clue has been located and searching in a "spiraling out" pattern. It is best to use an experienced tracking/sign cutting team to avoid destroying clues such as tracks. This tactic can also be deployed to follow the contour of a hilltop working down, referred as a "contour search".

Sound Sweep: This tactic is typically used in conjunction with other tactics like area and route searches. A sound sweep may be conducted by an individual team without coordination. However, if multiple teams are in the field, synchronized sound sweeps will be coordinated by Incident Base by radio.

Purposeful Wandering: Grid searches are normally conducted by a line of searchers working parallel to each other in an attempt to search as much of the ground as possible. One approach to increase the POD for these techniques is to use "purposeful wandering" in which the searchers zigzag or weave through an area rather than move in parallel lines. By doing so, they increase their coverage by expanding the length of the travel path, and consequently, the time it takes to complete their assignment. It should also be noted that if searcher separation is more than 2X the AMDR, the opportunity for areas not to be covered does increase. The search should still be conducted by having one searcher form a guide line of trail tape and walk a straight bearing.

Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT) Searches

Though not a search tactic per se, searchers should be aware of what is called an ELT search. In the case of aircraft accidents, a very rough landing or related incidents, the aircraft’s ELT transmits radio signals. On newer ELT models, a UHF signal is transmitted to a satellite which can then provide coordinates for the ELT signal. This can significantly reduce the search area and make a find much quicker. On older ELT models, a VHF signal is transmitted with no corresponding satellite detection and location. In this situation, the search area can be very large.

The Incident Commander, notified of an ELT signal in his/her district, may contact the Area Commander to obtain air resources such as the Civil Air Patrol, State Police and/or Guard helicopters to narrow the search location. The Incident Commander may also call out specially trained ground teams using equipment that can receive the ELT signal and triangulate to determine the location of the aircraft.

5. FINDING AND HANDLING CLUES

The "Searcher Cube": While moving through the search area you must search the entire searcher cube around you. That is, you must look all around you; left, right, up, down, and behind. An important clue, or even the missing subject, might be obscured from view when it is right next to you, but clearly visible after you’ve passed it. If you don’t turn around, you will miss it!

Practice searching with your team by laying out clues through an area and taking turns walking through the area looking for them. Experience shows searchers spend a disproportionate amount of time looking forward and to the right. They miss clues as a result.

Clue Awareness and Basic Tracking: You must be alert to clues subjects leave behind as they move through the search area. There may be only one subject, but there may be many clues. Concentrating solely on finding the subject may lead you to neglect important signs, such as:

Footprints are by far the most common clue left by a subject. It is not always obvious that footprints found in the field belong to the subject. With some up-front homework, it is often possible to determine the type of footwear (size, sole pattern, etc.) worn by the subject and thus better qualify the clues.

Here are two helpful tricks for locating footprints:

Use a raking light: Hold a flashlight or your headlamp as close to the ground as possible with the beam pointing out in front, allowing the beam to illuminate the ground at a shallow angle. Doing so causes the edges of the footprint to cast longer shadows, thereby placing it in sharp relief and making it more visible.

Look for track traps: Track traps are areas where the ground conditions are particularly conducive to creating and holding footprints. Good traps are soils of uniform, fine texture and without a lot of other clutter such as rocks and branches. Examples include soft, moist soil; sand; and ant hills.

The search techniques of tracking and sign-cutting require a very high level of clue awareness. While attaining these skills takes a great deal of training and practice, they have tremendous value.

Tracking refers to following marks made by the subject as he moves over the ground. In addition to footprints, marks might include tall grass bent over in the direction of travel or a path of disturbed dew or frost on the ground.

Sign-cutting refers to traveling around an area where the subject is trying to be contained, looking for evidence that the subject has crossed this boundary.

These techniques may be used as part of a containment/confinement strategy, as well as in area and hasty searches. If tracks can be found at a containment point and attributed to the missing subject, his direction of travel can be established. Resources can then be shifted to areas adjacent to the original containment area.

Handling Clues: If you find a relevant clue:

First, determine whether the object you find is something relevant. For example, finding a cigarette butt on a search for a missing young child is not generally a cause for excitement, nor would be finding a beer can during a search for someone known to have been hiking with only a water bottle.

Second, don’t disturb the clue. Report the clue to Incident Base; they may ask you to provide a GPS fix of the item’s location and/or mark the clue for other resources to investigate. (See Chapter 5: Map and Compass for a discussion of GPS receivers and how to use them.)

Mark around the object, without disturbing it, using brightly colored trail tape. In addition, hang a long piece of trail tape from a nearby tree or other feature so that it can be seen easily by approaching personnel. Write the date, time, mission number, and your team call sign on the streamer. Marked in this way, it should be easy for other teams to find the item. It will also prevent the same clue from being reported to Incident Base by other teams.

In some cases you may be asked to bring the clue to Incident Base. If so, you should certainly record the position where it was found, e.g., using a GPS receiver, and mark its location as discussed above. If the clue is to be used as a scent article for tracking dogs, special precautions must be taken to avoid contaminating the item. In that case Incident Base will instruct you how to proceed.

You may also be asked to photograph the clue. If so, include in the photograph an object that will show size and scale. It can be extremely difficult from photographs to determine the size and how an object is oriented unless there is some reference point in the photograph. A simple plastic ruler or other known size object can help investigators during the course of the incident. Another good item is a small plastic arrow to indicate north in the photograph. You should also record the date and time the photograph was taken.

6. DEATH SCENE

Unfortunately, you may come upon the search subject after he or she has died. If this happens to you, preserve the location as if it were a crime scene and immediately notify Incident Base.

When calling Incident Base, you should use the death code given to you at your briefing. (See Chapter 2: Communications for further discussion about the death and other codes.) The code conceals this sensitive information from anyone who might be listening on radios or scanners, i.e., the media and the family. This prevents news of the subject’s death from being disclosed inappropriately. The first word that a family member has died should not come from the television news or from a reporter asking the family for comment.

If your team comes upon a subject believed to be dead, only one team member should approach the body. It is best if the person doing so has medical qualifications and/or is the team leader. The remainder of the team should stay well away from the scene and not trample any clues that might remain. Once the investigating searcher has confirmed that the subject shows no signs of life, that person should withdraw from the body using the same path used for approach, rejoin the rest of the team, and tape off the approach to, and if possible completely around, the scene. The death scene area must be protected.

It is a good idea to have a small disposable camera in your pack in case you are requested to take photographs of the death scene. This photographic information will be important to the field investigator from the New Mexico Office of the Medical Investigator (OMI) if he or she cannot go directly to the scene.

No one should move the body or clues until the OMI field investigator has approved the removal of the body, either directly or through the State Police. Also, a State Police officer may need to actually see the body and scene before the body is moved.

Upon return to Incident Base, keep in mind that family members may be present so comments or discussion regarding the death scene should be handled only in the presence of Incident Base staff and with extreme discretion.

7. DEBRIEFING AND SIGN-OUT

At the conclusion of you team’s assignment, you will be debriefed by a member of the Incident Management Team (IMT). It is at this point that you will be asked if your assignment was completed as prescribed, suggestions for future searches, hazards in the area, etc. After debriefing, you may be given another assignment or released. When released, be certain to sign-out on NMSAR Form 211. The IMT will remain at IB until all personnel have been accounted for.

8. SUMMARY

Effective searching requires far more training and practice than most of us commonly assume. The dedicated SAR professional, paid or unpaid, should make every effort to study these skills and practice them regularly. Set up mock SAR missions with other area teams to increase your skill level. Contact specialty SAR teams to come and teach their specialty, e.g., high angle technical rescue, or tracking.

The art and science of searching has been changing over the years, so the continuous review of new material is highly recommended.

Here are some documents that provide additional incite into this subject: