After 2 million years of human evolution, backpackers think they're smart enough to keep their food away from bears. Yet, as we invent more and more clever ways to protect our food, it takes the bears only a season or two to outsmart us. Which is whv there are new rules for food storage in many of California's most popular backpacking areas. (It's only common sense to protect your food even without rules.)

It's not just a nuisance to lose food to a bear---it's illegal, and you may be subject to a citation and fine. The consequences for the bear can be even worse. For starters, human food is unhealthy for bears. Even worse is the fact that bears in National Parks and National Forests that become accustomed to human food will raid campsites every night---leaving the Rangers with two options: remove the bear or kill it. If removal doesn't work, the bear is killed.

Losing food to bears is almost entirely avoidable. It's never acceptable to lose your food or trash to a bear. Remember that wildlife, bears included, need only one thing from us: to be left alone. Anything you can do to minimize your contact or interaction with bears is a good thing.

Where the bears are

It's not true that there's a bear behind every tree in the Sierra. At least half the trees don’t have bears. In fact, it's quite common to go on a nine-day hike and never see a bear.

In the Sierra and other California mountains, bears are typically found between 1500 and 9000 feet, usually below tree line—though they have been sighted at almost every elevation. California bears belong to the “black bear” species (though they can be black, brown, or even blonde in color).

Most bear encounters occur where too many people regularly camp or on heavily traveled routes. A route that takes you away from the most popular sites, expecially off-trail and to high elevation, will greatly reduce the likelihood of an encounter with Bruin Hilda and her clan.

Camp care

To reduce the odds of attracting a bear, and for the benefit of other campers who may follow, keep a scrupulously clean camp. Pick up spilled food; carry it out. Wash off rocks, branches, or other surfaces to dilute any remaining smells and tastes. Do your kitchen clean-up well away from camp. Take the hot water, soap, and scrubber on a two- to three-minute walk uphill and away from camp, lake, and stream.

If there are food scraps left over, put them in your trash bags to carry out. Do not bury food; it just gets dug up later. Before bedding down for the night, take a final look to be sure there are no scraps or wrappers on the ground.

Bears are mostly nocturnal. You're much less likely to get a visit during the day. Still, never leave food or trash lying about even during the day. Bring out food only when you need to prepare meals.

When a bear comes calling

If a bear does come near your camp, act quickly to get it out. Stand tall, shout loudly, bang pots, and get everyone in your group to join you. Throw small rocks at the bear's haunches. (Do not aim for its head. A group recently killed a young bear this way.) Let the bear know in no uncertain terms that it is unwelcome. This will be highly effective in deterring the bear.

Bears usually show up at night, when you're fast asleep in your warm sleeping bag and loathe to get out into the frigid night air. Get up anyway---right away. The safety of your food and your party may depend on it.

Protecting your food

Your method of protecting food (including trash, toothpaste, sunscreen---any smelly items that may attract bears) will depend on the length of your trip and the number in your party.

Any storage technique is only a delaying tactic, though. Bears are clever; unless you chase them away when first spotted, they are likely to find their way into your food.

The "hunger march." If you leave food on the ground, covered with tarp and rocks, or in your pack, hoping that bears will not bother you, or that you will hear them in time to chase them away -- well, good luck. At lower elevations this method is likely to turn into a hunger march.

Bear watch. Some groups have put all packs and food in the center of camp and had two people stay awake at all times, talking aloud and using their obvious presence to keep bears away. This method can be highly effective if you know a bear is nearby; for example, when we've already chased it away. However, this method takes a toll on the group, requiring regular rotation of the watchers, lest they fall asleep.

Bear boxes. At all established campsite on a major trail the Park Service or Forest Service may provide a steel bear box. These are very effective. Place all food items in the box as soon as you arrive, and understand how the clasps work to lock the box. Do NOT leave trash or unused food in the box ... carry it out.

The top of the box is a perfect cooking surface. Rangers can tell you where the boxes are, and you can plan to camp near them. But you must be prepared to share them with nearby campers. Ask about locations when you get your Wilderness Permit.

Garcia food canister. This plastic canister is a very secure defense. The price is now about $80, but it can also be rented at many trailheads. The canister holds 10 qts, is 8.8 x 12 in, and weighs 2.7 lbs. It fits (awkwardly) in a backpack.

With hyper-efficient packing and repackaging you can get by with 1.5 canisters/person for an eight-day trip.

These "cans" are nearly indestructible by bears, though Rangers in Yosemite have seen bears roll Garcia cans off cliffs and feast on the disgorged contents below. (For bears, Yosemite is a lot like Berkeley: the spawning ground for cultural innovation.)

NOTE: The use of "canisters" may be REQUIRED in some areas. Check with the Rangers when planning your trip. Go to www.recreation.gov to find the web site for the area you will be visiting and then check that site for their rules.

Click Here for information about Bear Resistant Food Containers.

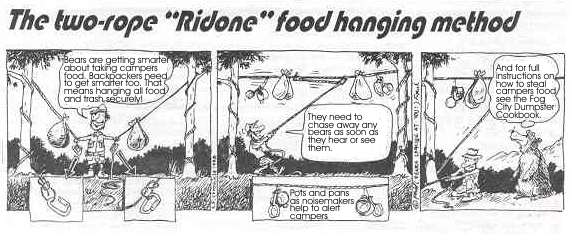

Hanging your food. Probably most backpackers use some method of food-hanging (aka "bear-bagging"). When you're camped near trees, and the branches are willing, these methods can give you a decent buffer of time to respond to a bear.

The tree should be near enough to hear and defend quickly, but away from your sleeping area (so that you don't get trampled) and cooking/eating area (to avoid attracting bears with food smells).

To alert you when a bear starts tinkering with your food, hang metal noisemakers (pots, lids, Sierra Club cups, ladles, etc.) on the rope before pulling the food up.

"Counterbalancing." This is the most common rope method, described in detail in practically every backpacking book.

Counterbalancing involves dividing your items roughly equally into two nylon stuff bags, throwing a rope over a limb, tying a bag to one, end of the rope, pulling the bag up to the limb, and then tying the second bag onto the rope, up as high as you can reach.

You then push up on the lower bag with a stick until it's even with the first bag, and you retrieve the bags by pulling with the stick.

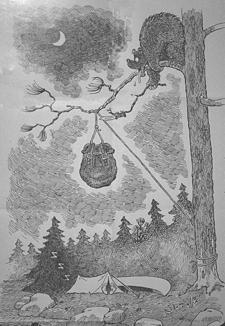

It can be hard to find a suitable branch---a cub can crawl out on the limb and down to the food. Bears learn to look for food hung close in to trees. Bears can LEAP from the trunk to the food. Cubs will piggy-back on momma bear's shoulders.

The down side to this method is that it's pretty tough on the tree branches; rope friction can strip off the bark. Thicker ropes do less damage to trees.

Two improved methods of hanging food

The "San Diego - one-rope, small-quantity method

This method works well with up to about 100 pounds.

The two-rope, double-carabiner "Ridone” method

The good news is that this two-rope method is a better way of suspending food between two trees. It works with nearly any tree, because any stub or broken limb jutting out will do---and it gets the food quite high, away from the trunk.

The bad news is that ideal trees with long, high, sturdy branches are often unavailable. (See illustration, below.)

Andy Johnson has led over 20 backpack trips for the Sierra Club since 1981, and never lost food to a bear on any of them. He has had plenty of experience jumping out into the cold night air, buck naked, shouting and yelling at bears.

Credits. Jean Ridone (Eugene., OR), rope methods. Inside Outings Newsletter, first publication of Ridone methods and images. These articles were also published in the July 1998 issue of the Sierra Club Bay Chapter’s Yodler